History, Connections, and Conservation at the Taipei Zoo

TEXT / JENNA LYNN CODY

PHOTOS / VISION

For over a century, the development of the Taipei Zoo has been intertwined with the history of Taipei, from its origins during the Japanese era to the beloved animals it has housed. The zoo celebrates its 110th anniversary this year, making this the perfect time to showcase its contributions to wildlife conservation and biodiversity in Taiwan and abroad.

Note: This article was published in the 2024 Autumn Edition of TAIPEI magazine, a publication by the Taipei City Government.

Taipei Zoo

The city’s zoo is a popular day-trip destination for tourists and Taipei residents alike. Today situated in the Muzha neighborhood of Wenshan District, close to the tea plantation area of Maokong, the zoo hasn’t always been in this location. Older Taipei residents remember the original site at Yuanshan in the city core, not far from the Grand Hotel Taipei. Originally a private zoological park owned by a Japanese resident, the site was purchased by the Japanese government in 1914 (during which Taiwan was under Japanese rule) and named the Maruyama Zoo after the Japanese name for Yuanshan. In 1946, the zoo was officially taken over by the Taipei City Government, and in 1986 was moved to its current location to allow for expansion. It is now conveniently accessible via the MRT Taipei Zoo Station.

The zoo encompasses 165ha, 90 of which are open to the public. In addition to the Children’s Zoo, which includes farm animals such as Lanyu (Orchid Island) pigs, there is the Insectarium, the “Bird World” aviary, the Amphibian and Reptile House, as well as habitat zones for temperate, desert, rainforest, African savannah, and Australian animals. Particularly popular areas include the Giant Panda House, Penguin House and Formosan Animal Area, which includes clouded leopards, Formosan black bears, Eurasian otters, and sika deer. Also visited by many is the Pangolin Dome, which gives visitors a close-up look at rainforest animals such as the scarlet ibis, two-toed sloth, cotton-top tamarin, and two types of tortoises. One can also walk under the unique Arapaima Pool to see arowanas, stingrays, and other Amazon River fish.

Through the years, the Taipei Zoo has been home to many notable and publicly beloved animal stars. These include Lin Wang, an elephant who served in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and famously lived to a very old age. Lin Wang featured in a prominent storyline in the acclaimed novel The Stolen Bicycle by Wu Ming-yi, which was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize 2018. The zoo has also been home to Baobao, a silverback gorilla eventually sent to the Apenheul primate park in the Netherlands to aid his socialization. Another unique resident is Kulong, which means “cool dragon” in Mandarin. Kulong is a tomistoma – a crocodile-like reptile with a long, narrow snout – who is said to wag his tail for humans he knows and likes. Other famous zoo residents are the giant pandas: Tuantuan and Yuanyuan, who were gifts from China, and their children Yuanzai and Yuanbao (note: Tuantuan passed away in 2022). In recent years, Malay tapir calves born at the zoo have become internet sensations as well. Every time one of these adorable creatures turns a month old, the zoo will hold an online naming contest, attracting participants from the general public, including celebrities and influencers.

Animal Behavior Academy

On Sunday mornings, people of all ages make their way through the Children’s Zoo to a small amphitheater. Waiting for the doors to open at eleven o’clock, they watch lemurs play in the tunnel connecting their habitat to the stage inside, and a parade of geese may pass through, waiting to be fed. Around the amphitheater’s tiered seats, rope ladders and branches allow the animals to climb and scamper.

Once seated, the audience is reminded by zookeepers of the ground rules: secure your belongings, avoid loud noises that might make the animals nervous, don’t touch any animal that seems curious about you, and most importantly, don’t be scared – and indeed, when I looked around during a recent visit, some of the attending children seemed a little nervous!

The animals are then introduced one by one. Lemurs from the habitat nearby climb above. Audience volunteers – usually children – are allowed to feed chickens, Lanyu pigs, an alpaca, and a miniature horse. Lemurs, meerkats, snakes, raccoons, and a clever sunflower-crested cockatoo may also make appearances. While seeing the animals up close, the zookeeper teaches the audience about each one, including anatomy, adaptation, climate, and locomotion, with an audience question-and-answer period at the end. Visitors may learn, for instance, how the cockatoo can hold a carrot in its claws, how raccoons use their dexterous paws, and how alpacas make use of their three stomachs.

The Animal Behavior Academy not only seeks to teach humans about the animal world, but also to socialize the animals who participate: that is, to get them more comfortable around humans. The program takes a principled approach in which animals are never forced or unnaturally trained to perform for audiences. Instead, each animal is encouraged to come out and interact in ways that align with their instincts, with some positive reinforcement of their natural behaviors. Raccoons are encouraged with snacks they would naturally be drawn to, and lemurs given space to climb of their own volition. As such, which animals join the event may differ slightly each time.

Entry to the Animal Behavior Academy is free with admission to the Taipei Zoo. Sessions are approximately 30min long and are held in Mandarin.

Animal Conservation

Like most zoos, the Taipei Zoo is more than a tourist attraction; it’s also devoted to animal conservation, rescue, and biodiversity. Many of the animals native to Taiwan and popular with zoo visitors are also vulnerable or endangered. These include the Formosan Black Bear, Clouded Leopard, Leopard Cat, Formosan pangolin, and Eurasian otter. The Taipei Zoo not only engages in conservation efforts to increase the captive population of these species but has also been building a “rewilding” program to reintroduce some animals to their native habitats.

Pangolins are among the zoo’s most famous denizens, and conservation efforts have been particularly successful. Chinese Pangolins, which inhabit both Taiwan and China, are a critically endangered species (Taiwan’s edition is a subspecies). They are illegally hunted for their meat, scales, and claws, making them one of the world’s most trafficked mammals.

Unfortunately, pangolins are known to fare poorly in captivity, which can confound conservation efforts. “Pangolins eat ants and other insects in the wild, but in captivity, we can’t feed them enough insects, as we can’t get them from the wild,” notes Eve Wang, the Taipei Zoo’s General Secretary.

However, zoo conservationists came up with a solution: a formula, created and perfected through cooperation with animal experts at National Taiwan University. “Now…we have some mating, we have offspring,” Wang states. “It all comes from a good formula. We now have twenty individual pangolins, so it’s quite a successful case.”

Other conservation efforts are less obvious. For example, the Taipei Zoo collaborates with other institutions to monitor wetland fauna and conserve habitats, among other goals boosting the population of frogs in the Taipei area.

The zoo also operates a rescue center as part of its animal conservation efforts. Due to the targeted nature of its endeavors, it is not open to the public. Many of the animals under care have been confiscated from individuals engaged in raising wild animals illegally, or at customs facilities as people attempt to smuggle them into Taiwan. The zoo works closely with the Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency in deciding post-rescue steps.

“Some animals rescued from customs are very weak or in poor condition. The mortality rate is high in the beginning, as some have long-term injuries,” Wang points out, stressing the importance of public education to stop poor treatment of animals. The majority of the animals taken in by the rescue center are reptiles. “In Taiwan, some people like to keep unique reptiles. They look unique and they’re easy to carry. Some people like to collect animals, but this is not good for animal welfare.”

Devoting to Rewilding

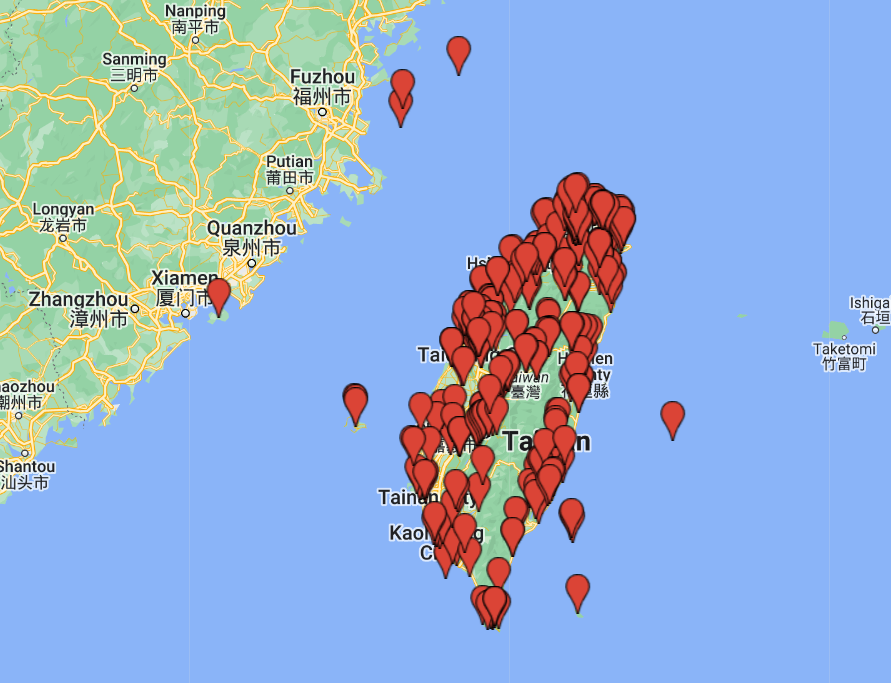

In recent years, the Taipei Zoo has made great efforts to reintroduce members of endemic species to the wilderness. The zoo has rewilded leopard cats and pangolins and hopes to do the same with Eurasian otters soon. The rewilding process is long, as animals in the program must be trained from birth. With a steadfast commitment to rewilding, the zoo is celebrating its 110th anniversary by focusing on 13 key species and their habitats. Dedicated to preserving biodiversity and inspiring visitors, it provides high-quality care for its animals and collaborates with conservation partners worldwide, aiming to reverse the trend of species endangerment and restore wild spaces for future generations.

International Cooperation

Animal conservation is often a cross-border effort. To increase endangered species populations, zoos frequently cooperate on innovations in care and breeding techniques as well as engage in animal exchanges, with the animal’s interests in mind. This isn’t only done to give visitors to the zoo more animals to see and learn about; it is a crucial vector for maintaining biological diversity in captive populations, where maintaining 90% biodiversity over a century is the goal.

The Taipei Zoo has been a proactive collaborator with other zoos and organizations around the world. These include the U.S.-based Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and the European Association of Zoos and Aquariums (EAZA). As its pangolin conservation program has been so successful, the zoo has given pangolins to such institutions as the Leipzig Zoo and Prague Zoo. It has also made significant contributions to gorilla biodiversity, first in gifting the silverback Baobao to the Netherlands, where he afterward established a family, and later working with the European Endangered Species (EEP) program to integrate a male gorilla from Poland and two females from the Netherlands in Taipei, where they too have produced offspring.

Wang explains, “Gorillas have to be in a family for six years and be taught by their parents to ‘be a gorilla.’ Individual male gorillas will fight, so it’s better to have a family. Baobao is happy now, he has a child. Here in Taipei, we need to ensure a suitable habitat for the gorillas as well. We’ve developed a comprehensive ten-year plan to establish a thriving gorilla family.”

The Taipei Zoo also cooperates closely with Japan on exchanging a variety of animals, including red pandas and tapirs. Unfortunately, tragedy has struck in one case. Earlier this year, a Malaysian tapir named Hideo, from a zoo in Yokohama, was pronounced dead on arrival in Taiwan.

“Everyone is heartbroken,” Wang said. “Because we treasure the relationship, we don’t want to blame anyone. In the future, we may need more checkpoints and checklists, and if the Japanese zoo officials feel comfortable, we can check everything together.” This incident will certainly not change the zoo’s commitment to collaborate with other zoos in the future, but it will serve as motivation to be even more careful in the future.

Japan has also given Taiwan a male red panda named Weilai, which means “future,” with the hope that it might breed with the Taipei Zoo’s female red panda. Wang comments, “We encourage natural breeding, but it has failed many times, because Weilai and our female don’t have the experience. However, we encourage them to have a ‘future’!”

Going forward, the Taipei Zoo will continue to work closely with international zoos and associations to bring Taiwan’s positive contributions in animal conservation, breeding, and biodiversity to the global stage.

110th Anniversary of Taipei Zoo

The Taipei Zoo has organized several events this year to celebrate its 110th anniversary. Some of these have been international in scope, aiming to reverse global biodiversity loss. Locally, themed MRT carriages have been unveiled. The 110th anniversary day falls on October 26, and a grand celebration will be held that day on the zoo’s main plaza, featuring performances by the children’s choir of the Taipei City Indigenous Peoples Commission and a market organized by corporate partners, including the Taiwan Association of Zoological Park and Aquarium, partners based in the Maokong area, schools, NGOs, and other organizations. Other events and activities are planned throughout the month.

About the author

Jenna Lynn Cody

Jenna is an American woman living and working in Taipei, Taiwan.