A Varied and Meandering Wander on Yangmingshan’s South Side

TEXT | AMI BARNES

PHOTOS | VISION

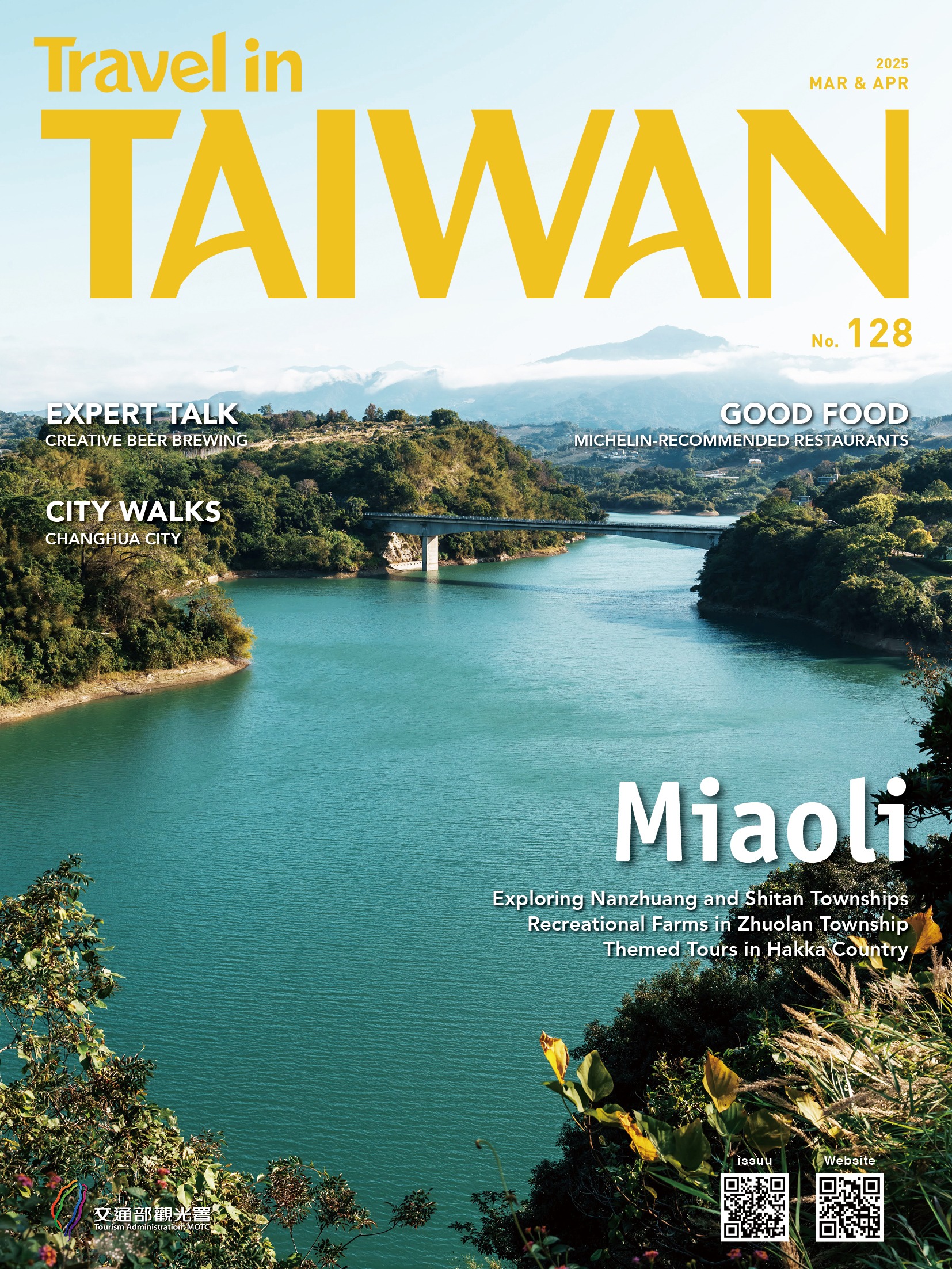

The Yangmingshan massif on Taipei’s north side, home to Yangmingshan National Park, is one of Taipei’s greatest natural and scenic assets. Its wild corners and manicured gardens offer hikers a playground, nature enthusiasts a classroom, photographers a muse, and fitness fans a gym. What’s more, accessing all of this could hardly be easier. Convenient transport connections link downtown Taipei with its green spaces, and many walks – such as the one featured here – start right from the city’s urban fringes.

Note: This article was published in the 2025 Spring Edition of TAIPEI magazine, a publication by the Taipei City Government.

We start our hike near the northern end of Section 7, Zhongshan North Road, in the Tianmu neighborhood of Beitou District.

Tianmu Historic Trail is not one of those walks that eases you into the swing of things. Leaping off into the greenery from Tianmu’s sleepy residential shoulder, it commences with a thigh-burning, lung-straining ascent up stone steps – around 1,300 to be precise. Old brick and stone dwellings line the first couple of hundred meters. Their courtyards are filled with quilted jackets and faded vests, hinting at silver-haired residents – presumably, particularly hardy silver-haired folks if they have to lug their weekly groceries up these steps.

Further up, allotments boast beds of cabbages, taro, and beans, while banana palms and bamboo grow on steep scruffy terraces. On a recent foray, every couple of hundred meters I spotted wooden brooms leaning against a tree trunk or wall, left there by the early risers whose morning visits involve sweeping the trail clear of leaves and other debris. When I passed through at 9:30am, the sweepers had long since been gone and the path had already begun amassing their leaf quota for the next morning.

After about 20 minutes of climbing, the steps bring you to the old black water pipe that gives this route its alternative name – Tianmu Water Pipe Trail. The steel structure is so large that it would be impossible for your hands to touch if you tried hugging it. The first version was a ceramic pipe installed during Taiwan’s period of Japanese era (1895~1945) as part of the Grass Mountain Waterworks – a project initiated to supply Taipei with both water and hydroelectricity. These days, Taipei meets its water and electricity needs elsewhere, but a faint susurrous of running water still emanates from the pipe.

Hikers briefly climb in lockstep with the water pipe. The steps then level out beside Zizai (Carefree) Pavilion, and besides where many walkers pause to catch their breath or fill up their water bottles, the pipe dives beneath the trail on its way to meet a pumping station.

Make your way uphill from the pavilion towards Alley 4, Lane 61, Guanghua Road. Just before you hit the road, the trail swings left and embarks on the most relaxing portion of the day’s adventure. A broad gravel track hugs tight to the hill’s contours, stretching out under the generous shade of a mixed broadleaf forest. The path is flat and easy to walk – a happy byproduct of having a water pipe buried beneath the trail.

This spot is also one of Taipei’s most reliably successful monkey-spotting locations, with the resident troupe of some 20-plus Formosan macaques often seen lounging on rocks or fences at either end of the day. In recent years, public education campaigns have helped reduce human/monkey conflicts to near zero, but it’s still worth reiterating that – like all wild animals – they should be treated with due caution.

The righthand side of the trail is bordered by a towering andesite cliff, an impressive feature – bluntly named the “Big Rock Face” – upon which lichens and a few hardy plants have created abstract-art masterpieces. To the left of the path, the distinctive twin-bumped dome of Mt. Shamao can be spotted in the distance, while even further away, a sandy scar gives away the location of Beitou District’s Liuhuanggu (Sulfur Valley) Geothermal Scenic Area. And speaking of sulfur, as the trail rounds a bend to head northeast, a faint whiff of the pungent mineral hangs in the air, evoking the happy promise of a hot-spring soak awaiting you at the end of your journey.

If you’re looking for a short, slightly adventurous side sortie, take a detour to the following secluded waterfall.

Leaving the rockiest part of the rock face behind, look out for an unmarked flight of steps darting into the trees on the left (if you pass a pavilion with seating, you’ve gone too far). This optional diversion leads to Cuifeng Waterfall (it takes about 30 minutes to get to the waterfall and come back). It is considerably more rugged than the rest of the walk featured here, and as such should only be attempted by those in possession of a sturdy pair of shoes and an intrepid spirit.

Steps descend to a clearing, then a narrow dirt path – little more than an animal track – forks right. A rustic three-slab Earth God (Tudi Gong) shrine guards the woods here. Time has faded the shrine’s red banner, and the idol is riddled with beetles-bored cavities, but fresh incense ash indicates continued obeyances. Beyond the shrine, roots, ropes, and a scattering of long-ago-placed stones guide your steps ever downwards – all the while, the voice of the local creek swells from hiss to roar.

Cuifeng Waterfall tumbles through a tight V-shaped gorge, to land in a neat pool bounded by steep rock walls. The main flow is fulsome, if a little short, but by far the most eye-catching element of the scene is the rocks. They are orange. Red-brick, Crayola-crayon, middle-part-of-candy-corn orange. This bizarre coloration comes from the minerals present in the waters of Pine Creek, minerals which also turn the water into a cloudy yellowish hue. Viewed against nature’s regular palette of greens, grays, and browns, the orange rocks seem impossibly vibrant – as if someone has gone a little over the top with the Photoshop dials of reality.

For the second part of this hiking outing, we move on to walk up the interestingly shaped Mt. Shamao.

Once you’ve restored your inner peace with some waterfall-watching, it’s time to shake off the reverie and get moving again. Retrace your steps up to Tianmu Historic Trail, then keep following the path until it joins Lane 12, Aifu 3rd Street. Turning left, you’ll soon find yourself crossing a bridge over Pine Creek and walking up a short flight of steps to Shamao Road. If you’re beginning to flag, there’s an easy out here – just hop on a bus (from The First Scenic Lookout bus stop, bus no. 128 to MRT Shipai Station or no. 230 to MRT Beitou Station). But for those still full of beans, turn left and make your way along the road for about 350m to the start of the Mt. Shamao Trail, on the roadway’s right. At this point, you enter the confines of the celebrated 11,300ha Yangmingshan National Park, which takes up a good portion of the Yangmingshan massif.

Mt. Shamao is a small(ish) and near-perfectly formed lava dome named for its resemblance to an ancient Chinese official’s gauze hat. On a map, its tight concentric contour lines look like a kid’s attempt at free-hand circles, while in profile, the peak is a pleasing mound with a dimple at the center. In hikers’ terms, this translates to an ascent that starts steep and gradually levels off before sliding down an equally steep pathway on the far side.

Formosan sweet gum trees, bamboo, ferns, occasional cherry trees, and azaleas all add beauty and/or shade to the route. In spring, hikers’ steps are accompanied by the rustle and darting of skinks, and as the summer heat bears down, the trail thrums to the beating of butterfly wings. The mountain is also known for its significant snake population.

A 1.2km climb brings you to the summit, but just before you arrive, the trail passes the remains of the Taizi Pavilion. This structure was built ahead of the 1923 grand tour of Taiwan by Japanese Crown Prince Hirohito (posthumously honored as Emperor Showa). The Japanese authorities were keen to show their future emperor the natural beauty and resources of Taiwan, but Hirohito never graced the slopes of Shamao. The pavilion, though fit for royalty, was only ever used by civilians.

A wooden viewing deck caps the summit of Mt. Shamao and rewards hikers with panoramic views. On clear days, Mt. Qixing’s seven-spiked crown dominates the landscape to the northeast, at the foot of this mountain’s western slopes lie the flower fields of the Zhuzihu area, and to the west of that, Mt. Datun’s various peaks taper down towards the Tamsui River estuary. The views are good, but on the platform, it can also be relentlessly windy, so hold on to your hat!

The trail concludes at Qianshan Park, where buses regularly depart for central Beitou and Shilin destinations. However, it’s well worth exploring some of the park’s attractions before you head back down to the city. The public hot-spring pools, set to reopen this spring, are close to the trailhead. The pools are sex-segregated and free to enter, and bathers are naked save for an obligatory shower cap. If you’ve never been to public hot-spring facilities in Taiwan before and are unsure about the etiquette, fear not – the elderly locals who patronize these springs are generally eager to impart their advice.

For one final point of interest, head to the Wisteria Pavilion at the northern edge of the park. The wisteria season runs from March to April, so at the time of publication the pavilion will be dripping in a photogenic cascade of purple flowers – the perfect place to snap a triumphant “we made it” commemorative photo or two.

About the author