Exploring the Hakka Heritage of Urban Taichung’s Borderlands

TEXT | AMI BARNES

PHOTOS | RAY CHANG

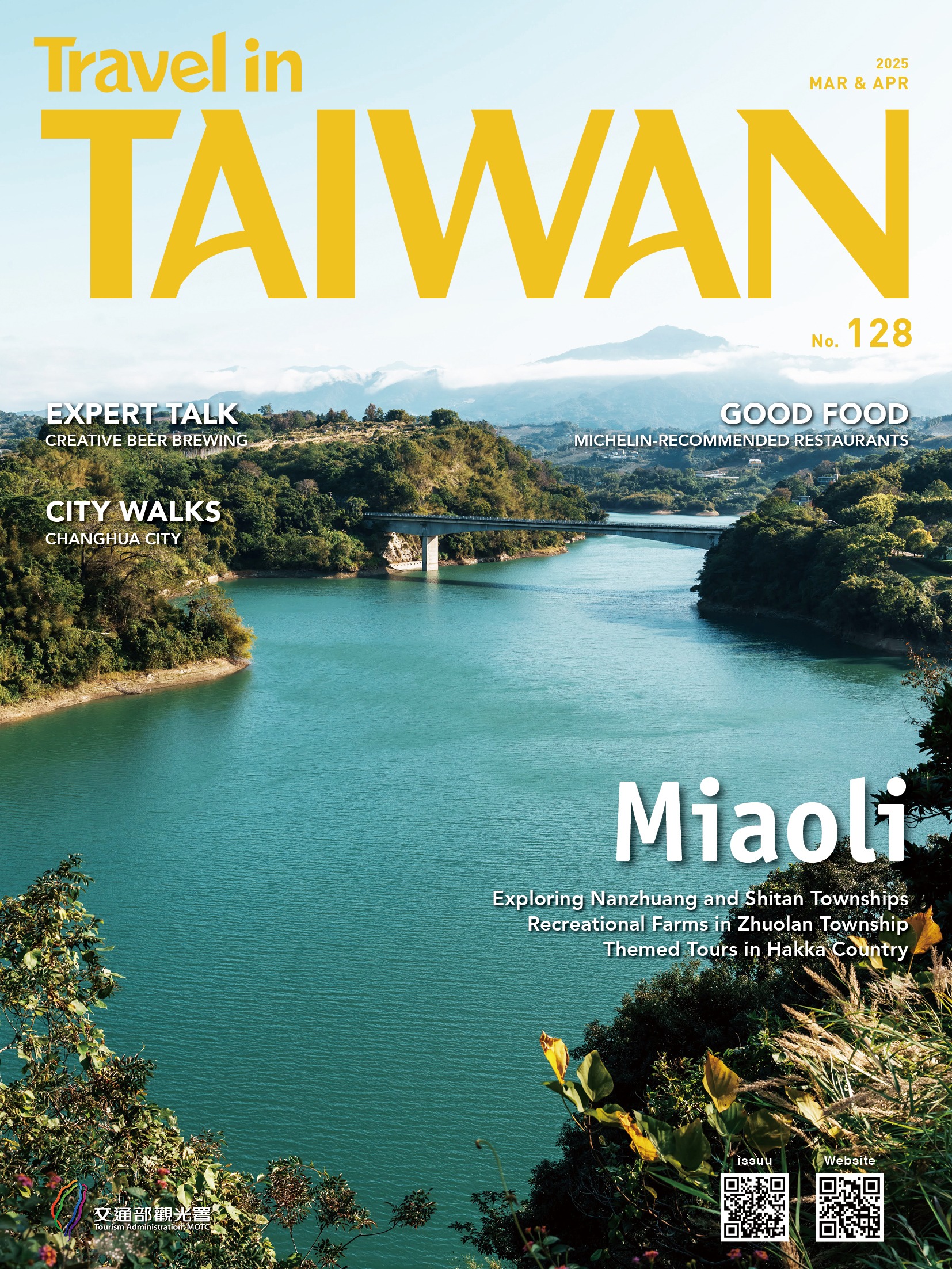

The districts of Dongshi and Shigang form a Hakka enclave at the border between Taichung City’s Hokkien-speaking coastal conurbation in the west and its mountainous area in the east. Just a short bus ride from the regional transport hub of Fengyuan Railway Station, here you’ll find heritage houses, curious temples, and a way of life that has remained little changed by the passage of time.

Dongshi Hakka Cultural Park

This park sits near the southeastern end of the Dongfeng Bicycle Green Way. Previously, this place was home to Dongshi Station, the final stop on the Dongshi Branch Line, and though the old station building was torn down long ago, those with a keen eye for the historical will spot several salvaged elements. The interior space of the rebuilt station building is broken up by the top-heavy columns that used to bear the platform roof, while outside, discarded sections of track have found a second life edging herbaceous beds and paths.

The park’s primary purpose is to serve as an active hub of Hakka culture, and to that end, the building is filled with displays introducing the local Hakka population. Surrounding the building are vendors selling drinks and snacks, plenty of photogenic Hakka-themed installations, and a side exhibit detailing the region’s camphor trading industry. This year, Dongshi’s annual Sindingban Festival was also held here – a fertility festival that sees residents compete in making creatively molded giant red turtle cakes to welcome new births (there are humungous wooden molds on display).

Dongshi Hakka Cultural Park | 東勢客家文化園區

Add: No. 1, Zhongshan Rd., Dongshi District, Taichung City

(台中市東勢區中山路1號)

Tel: (04) 2588-8505

FB: www.facebook.com/fantasy.dons

Tuniu Hakka Cultural Hall

A second Hakka highlight, the Tuniu Hakka Cultural Hall, can be found a 10min bike ride from the cultural park in Shigang District. Housed in a courtyard-residence compound belonging to the Liu clan – a prominent local Hakka family – the main buildings of the complex are by far the most impressive feature. They were reconstructed after the large 921 earthquake of 1999, and consist of three interconnected wings arranged around a courtyard. Out front, koi swim in a crescent-shaped pond, and dotted around the gardens, you can find a well, aged fruit trees, and a ritual-paper-burning pagoda.

Exhibits fill the side halls, while the central hall houses the clan’s altar, complete with ancestral tablets and imposing portraits of the founding paterfamilias. The displays cover some of the same points as those in Dongshi Hakka Cultural Park, but what this site manages to do well is show the artifacts in context using photos and videos. The exhibits provide an insight into how Hakka folk ate, lived, studied, and worshipped in the past – and judging by some of the more recent photos included in the displays, much of the culture remains unchanged. Indeed, the side buildings of the complex remain inhabited by Liu clan descendants.

Tuniu Hakka Cultural Hall | 土牛客家文化館

Add: No. 10, Decheng Ln., Fengshi Rd., Tuniu Borough, Shigang District, Taichung City

(台中市石岡區土牛里豐勢路德成巷10號)

Tel: (04) 2582-5312

FB: www.facebook.com/tnhakka

Damaopu Settlement

The Hakka identity is one that was forged in the fires of hardship and necessity. Migrating south long ago from China’s central plains, the ancestors of today’s Hakka often found their new neighbors reluctant to shuffle over and share the land, and consequently tended to end up eking out a living in inhospitable fringe regions. This gave rise to the persistent image of Hakka being a resourceful, hardy folk with strong intra-community bonds. It also left its mark on the group’s cultural practices and spiritual beliefs – particularly when it comes to customs governing the delicate balance between humans, nature, and space.

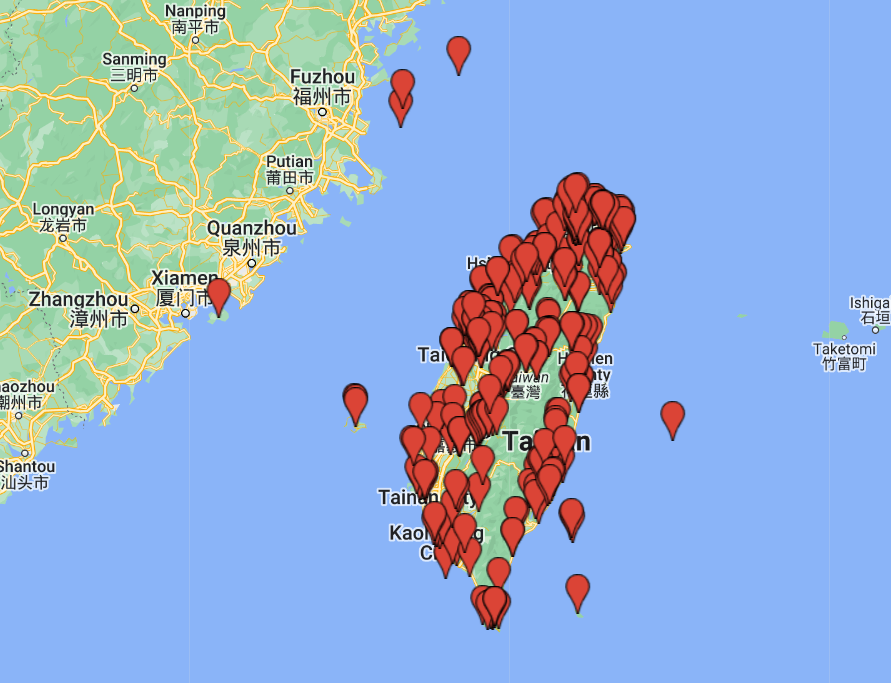

When Hakka pioneers began arriving in Taiwan in the 1600s, they brought with them a belief in dragons. As they saw it, the spirit of the land was embodied in dragon form, and when choosing where to build they sought out these dragons in the landscape, inviting the mythical beasts’ energy into their homes. Many believed the presence or absence of food in their bellies hinged on their ability to coexist harmoniously with these tutelary deities, and to this end, numerous rituals and standards were established. In modern-day Taiwan, the settlement of Damaopu in Dongshi District offers one of the best places to get a feel for what this looks like.

Before Hakka settlers moved in – in the early 1800s – this area was not exactly prime real estate. The animosity of the indigenous Taiwanese inhabitants and the lack of a consistent water source meant that the incomers faced hostilities both active and passive. Villagers built a thick living fence of thorny bamboo, a dense grid of streets, and a three-meter-wide moat to defend against the former, and the moat handily doubled as an irrigation canal, allowing the dragons’ wealth-bringing lifeblood to flow through the heart of the community.

Religious sites are a key feature of Damaopu. Taixing Temple – with its three altars sitting one behind the other – occupies the grid’s center, the focal point of village life, while around the outskirts you’ll find smaller shrines, serving as guard posts from which the generals of the cardinal directions provide spiritual protection. Elsewhere, there are several Bogong (Hakka name for the Earth God) temples and a Stone Mother shrine, the latter evidence of a unique Hakka practice that involves presenting colicky babies and tantrum-prone toddlers to these literal rock goddesses in the hopes that the deities will agree to shoulder a share of the parental burden.

Wandering around the village, glimpses into the quiet loveliness of daily life can be snatched at every corner. An elderly resident parked in a sunspot for a snooze; basketfuls of freshly pulled radishes awaiting a scrubbing; a row of tiny, well-dressed grandmas gathered for gossip while in another village corner the menfolk and their cigarette smoke fug huddle around a game of mahjong under a temple awning. This settlement is a study of the beauty of the mundane.

If this sounds like the kind of place you’d be interested in exploring, it might be worth looking into the Dragon-Searching Adventure tour organized by the Daomaopu Research Team. This activity has been designed to introduce people to the life and culture of Damaopu, and the Hakka community at large. The precise content of a tour varies depending on the needs or interests of a group, but it generally involves a guided walk with an emphasis on explaining how the village was shaped by Hakka beliefs as well as multisensory activities such as clam picking and tubing in the canals that allow kids to interact directly with the arteries of the settlement’s old dragons. At the moment, tours (bookable by phone) are better suited to educational groups than independent travelers since they’re only available for larger, Chinese-speaking groups of 15-20.

Damaopu Village | 大茅埔聚落

Tel: 0975-208-397

Website: romantichakka.com/en

Dragon God Mountain and Water Festival

Held each October, this is a one-day event welcoming outsiders to greet the town’s old gods. Festivities begin with mask painting, followed by a procession that sees Taixing Temple’s dragon deity borne aloft through the winding streets by masked participants, and the day culminates in the memorable sight of glowing, hand-folded paper boats sailing along the town’s irrigation canals at dusk.

About the author