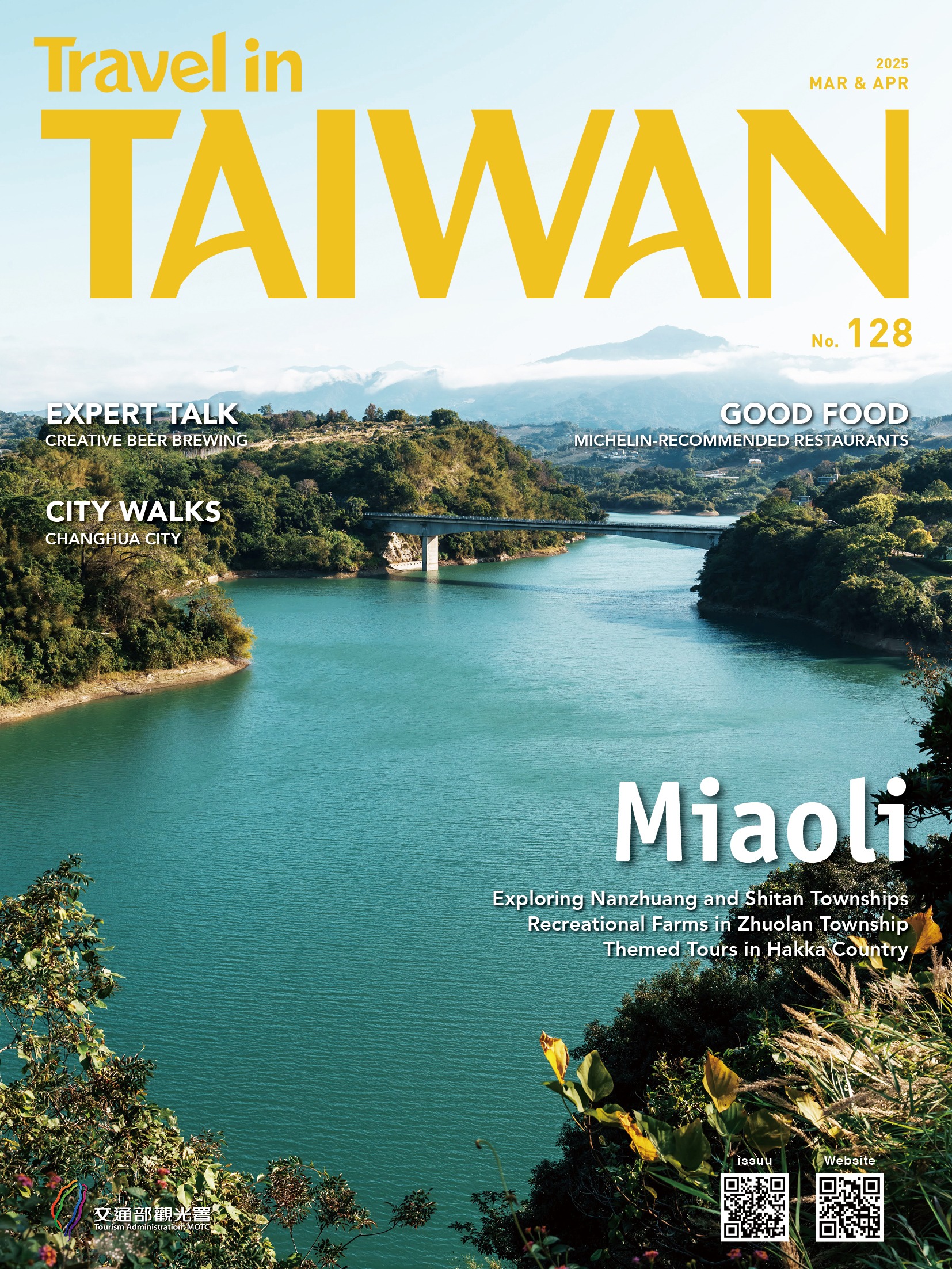

A Pick and Mix of East Taiwan’s Experiential Travel Offerings

TEXT | AMI BARNES

PHOTOS | CHEN CHENG-KUO, VISION

The counties of Hualien and Taitung in east Taiwan receive much love for their scenic beauty. Ask why you should visit, and you’ll be treated to breathless talk of marble-laced gorges, cliffs rising from an implausibly teal ocean, wild hot springs, and multi-day treks to alpine lakes – every word of it true. Less frequently cited but no less manifold are the immersive cultural experiences offered by this ethnically diverse region.

East Taiwan’s coastal terraces are considered to be the cradle of civilization in Taiwan. Artifacts discovered in caves and burial sites scattered among the hills hint at a period of habitation stretching back over 10,000 years, and among the descendants of those early inhabitants are members of the 11 different indigenous groups populating the region today. Over the centuries, they have watched waves of outsiders come and go and come and settle. Now, the region is one of the most ethnically diverse in all of Taiwan, and many native residents have found they can make a living by sharing their culture and way of life with open-minded travelers.

Hualien

Cidal Hunter School

“If only we had more time, I could spend a whole day talking about these,” our host Panay Falao said, gesturing at plants lining a 20m-long trail running between an outdoor classroom and an archery range. After a morning in her company, I had no reason to doubt her. Panay belongs to the Amis ethnic group (“Amis” is the name used by the government; members themselves prefer “Pangcah”), and as the co-founder of Cidal Hunter School, the reformed office worker is on a mission to preserve and share her heritage.

The ocean-facing school sits on the low slopes of the Coastal Mountain Range just outside Shoufeng Township’s Shuilian (Ciwidiyan) Village and is a 40min drive south of the city of Hualien’s center. Depending on what time of year you visit, Cidal has several different itineraries to pick from. They’re all bookable through the school website, which – like the on-site teaching – is Chinese-only, so enlisting the assistance of someone who can translate would be useful. Activities available include eco-printing, crab hunting, archery, village tours, traditional Amis meals, bushcraft courses, and even overnight stays. On a recent Travel in Taiwan visit, we were there for the half-day hunter survival experience, which aims to let visitors understand how a hunter meets all basic survival needs with nothing more than a knife.

I have to confess to holding a couple of unfounded assumptions before our visit. I was expecting something more superficial, and given that “hunter” is in the name of the school, I had also anticipated we would be learning primarily about hunting and killing – not something your vegetarian writer is too keen on. On both scores, I was happily proved wrong. This was no gimmicky tribal photo op – Panay was intent on ensuring we left better informed than when we arrived, and what’s more, since the Amis are famed for their skillful use of greenery, plants turned out to be the primary medium of instruction for this introduction to their culture.

Panay began our crash course by cleanly slicing off several heart-shaped elephant ear leaves from a patch of weeds beside one of the school’s buildings. Handing us one each, she asked what we thought it could be used for. Between us, we came up with a few ideas; maybe an umbrella, a seat, a plate, a hat. But no one guessed the use she had in mind: a water bottle.

With the right guidance, the transformation from leaf to water bottle is simple, even for novices. Holding the paler, cleaner underside facing towards me, Panay had me bend my leaf so that I could pinch the tip of its heart against the stem between my forefinger and thumb. With my spare hand, I then folded down one of the lobes, finger-walking it into scrunched-up pleats until there was no slack remaining, and repeating the procedure on the other lobe. At this point, the bottle had already taken shape, and Panay demonstrated how to fasten everything in place with a length of natural twine. Then came the moment of truth – dipping my vessel into a bucketful of water – and when I lifted it up, it bore a pleasingly heavy load. Of course, in a village with buckets at our disposal, this is hardly necessary, but such methods could easily come in handy when transporting water from stream to mountain camp.

Next up, we were introduced to shell ginger or yuetao (Mandarin pronunciation), a plant that grows all over Taiwan at low-to-mid elevations. Its extreme usefulness transcends ethnic divisions, and no matter whether you’re talking to indigenous or Han Chinese elders, they should be able to tell you at least one way in which it is used. Listening to Panay, though, it became a wonder plant with a million and one potential applications.

Snug rose-shaped knots tied using lengths of the outer layers form the basis of a mountain shelter. Before climate change pushed seasons off-kilter, its late-spring blooming was a kind of floral calendar, reminding coastal communities to ready their nets for the annual flying fish migration. Its leaves can be used to transport food and – like its flowers – make tea, while hunters in a pinch can sip the life-giving nectar directly. The seeds, rhizomes, and tender hearts all have aromatic or medicinal functions. In the hands of deft weavers, it can become all sorts of useful items. And, if you select the right piece of the sheath, you can make a small whistle that mimics the sound of a bamboo partridge well enough to lure in the territorial birds – although these days, hunters are more likely to use a cassette player to do the job.

Talk of turning to modern methods prompted broader discussion on how contemporary indigenous folk view themselves and their culture, particularly regarding tourism. Panay was quick to point out that if you ask fifty people for their thoughts on the subject you’ll get fifty different opinions, but for her part, she says that as long as visitors are willing to learn the significance of the artifacts or activities, then she is happy to share her culture.

Our schooling continued on the way to the archery range. We were introduced to the four important plant species found in the vicinity of every Amis community: breadfruit, longan, velvet apple trees, and betel palms. Between them, they meet the basic sustenance and ceremonial needs of a family. We also gathered fistfuls of fallen soapberries – so named because when wetted and rubbed vigorously between cupped palms, they soon produce a foamy lather that cleanses both bodies and clothes.

Down on the range, we met a village elder, teacher, wordsmith, and archery pro who was introduced to us as A-Long. With his handmade bow and a pouch full of slender wooden arrows on his hip, A-Long made it look easy, sending flight after flight into the center of a target decorated with a cartoonishly cylindrical boar. After retrieving them, he gave us a closer look and showed us notes such as “veers left” handwritten on the shafts to assist with aim and the modifications he’d made to ensure they flew parallel to the ground – when your arrows are made from bamboo, you’ve got to bend your technique to meet the materials halfway.

Capping off our visit, Panay showed us how to braid circlets from a section of coconut palm leaf, which we then donned for the obligatory memento photo. While this shot of us with bows poised and headdresses in place is definitely the most dramatic image from our time at the school, it is not the part that has remained with me. For me, the enduring memory is Panay’s deep understanding of her environment and her ability to reframe my perception of everyday plants through sharing her knowledge.

Cidal Hunter School

(吉籟獵人學校)

Add: No. 179, Shuilian Rd., Shoufeng Township, Hualien County

(花蓮縣壽豐鄉水璉路179號)

Tel: (03) 851-3990

Website: www.cidal.com.tw (Chinese)

Taitung

Imagine Taitung

Luye is a quiet, deeply rural township at the southern end of the East Rift Valley. The region’s scenery has a Ghibli-esque quality with blue skies, green mountains, and the occasional flash of orange-and-white-liveried express trains reflected in the mirror-like surfaces of paddy fields. An agricultural patchwork blanket of bananas, pineapples, avocados, guavas, loquats, custard apples, papayas, and dragon fruit each take their turn to swell and ripen, while on higher slopes tea pickers endure blazing sun to harvest leaves that will become Luye’s specialty red oolong.

Tourism here is something of an all-or-nothing affair. Every summer, thousands of visitors descend upon the Luye Plateau for the month-long Taiwan International Balloon Festival (balloontaiwan.taitung.gov.tw), while for the other 11 months, there are few outsiders. The founders of Imagine Taitung felt that this was a wasted opportunity. More specifically, they believed that the seasonal rhythms of agricultural life could form the basis of many an engaging slow-travel experience, and so the company was born. Initial offerings centered around connecting local farmers with curious incomers. That soon expanded to incorporate an online platform allowing small-scale producers to sell to a wider audience, and the final step involved establishing a physical headquarters to serve as a base for the farm tours along with a kitchen-cum-classroom where local produce could be explored in greater depth. These days the company’s cooperations allow it to cover an impressive variety of activities ranging from high-adrenalin adventures to handicraft workshops and several farm-to-table experiences.

During our recent Travel in Taiwan visit, we spent the best part of a day with Imagine Taitung and were able to take part in two of their curated activities. The first of these was centered around tea picking and tasting, designed to give visitors an introduction to red oolong tea. Despite having lived in Taiwan for a fair number of years and hailing from the notoriously tea-obsessed UK, I am essentially a tea-drinking neophyte. I’ve not been bitten by the bubble tea bug and have only been proactively frequenting drinks shops for the past year or so. Suffice to say, I had a lot to learn!

Tea picking is best done when the moisture content of the leaves is lowest. On dry days, this means pickers work from first light through the blistering midday heat, hence the industry’s unofficial uniform of a conical bamboo hat accessorized with sun-faded detachable sleeves. Cheer – our guide for the morning – helped us get kitted up, completing the look with squares of fabric folded into triangles and tied beneath our chins to keep the backs of our necks well covered. She showed us how to pluck off the tips – pinching just below the third leaf, snapping it up and away from the body. The motion seems simple enough, but imagine doing it all day and you can see how you’d soon end up sore. She explained that professional pickers get around this by taping blades to both index fingers, allowing for easy simultaneous two-handed picking. This method also enables them to pick more and pick faster – important for workers whose daily pay is measured by the weight of leaves collected. Being under no such time pressures ourselves, we meandered along the rows filling our bags until we had enough to use for the later tea-instruction class.

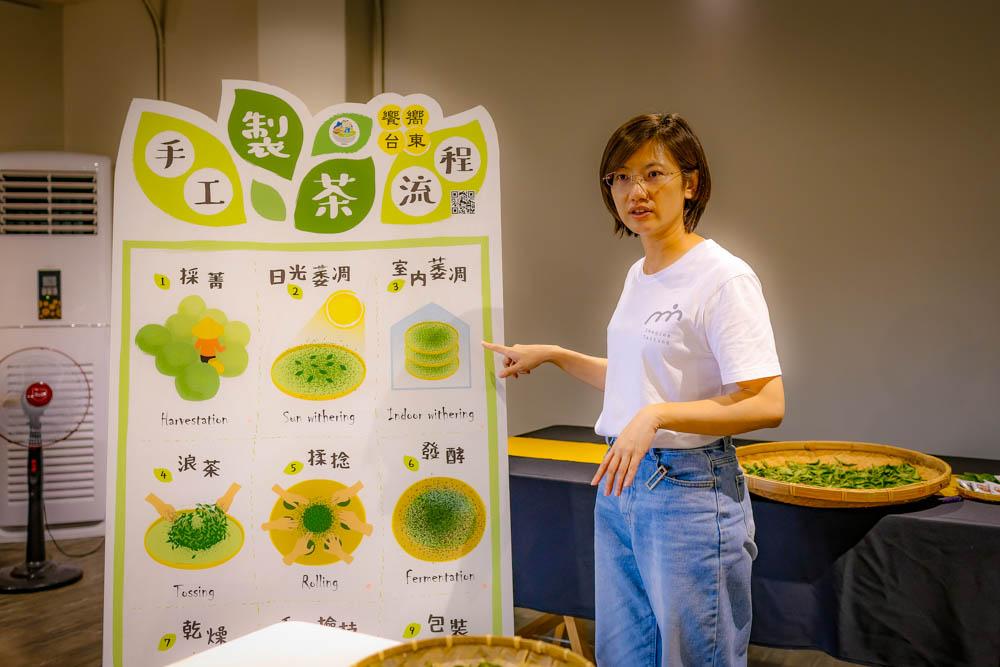

In Imagine Taitung’s second-floor classroom, we were schooled in the various production methods used for making different types of tea. Broadly speaking, teas in Taiwan are categorized into six types based on the color of the tea after brewing – white, green, yellow, red, black, and qing (a color that sits somewhere between green and yellow). The color is determined not by the cultivar of tea used, but by the order, types, and degrees of processes it undergoes after picking, and names such as oolong, pu’er, and oriental beauty are used to distinguish teas that have been processed following a specified set of procedures. Our leaves – we were told – were from jinxuan cultivar plants and would be undergoing light processing consisting of just two steps (withering and drying), resulting in a white tea. In contrast, Luye’s famous red oolong is made utilizing a multi-stage process involving withering, rolling, fermentation, and drying.

With the basics in the bag, we were then introduced to two types of locally made red oolong. Over a series of steepings, we were encouraged to explore how the tea’s scent and flavor progressed, how the mouth-feel evolved, how each steeping brought subtle differences in scent (honeyed pineapple, fresh florals, grassy), and how each taste activated different areas of the tongue. I still cannot claim to be a tea connoisseur, but I am confident in saying that I ended the day with a deeper appreciation for the nuances of the drink.

The second activity we tried our hand at was a farm-to-table pineapple jam-making experience. We followed Cheer’s car down ever-narrowing roads sandwiched between rows of fruit trees until we found ourselves rattling along the grassy track leading to Farmer Niu’s pineapple patch. Sporting a deep tan, a hat with an in-built mosquito net, and an age-holed T-shirt onto which he had stitched loose protective sleeves, Niu looked every inch the farmer.

Leading us deeper into the greenery, Niu explained that August is generally right at the tail end of the pineapple harvesting season, but that he’d left a few because he knew we’d be visiting. Unlike some of the neatly serried ranks passed on our drive, the farmer’s organic and pesticide-free patch was not instantly discernible. Blackjack and floss flower ran rampant between rows – the spiky forms of the pineapple plants only revealing themselves after a closer second glance. To pick them, we wore thick gloves and were shown how to grasp the fruit and twist while exerting a gentle downward force. The fruits came away more easily than I’d anticipated. So easily in fact that – at the risk of spoiling the magic of photography – I spent more time pretending to pick pineapples for the camera than I spent actually picking them.

The cultivar Niu grows is known as cayenne or native pineapple. Appearance-wise, they’re smaller and more spherical than the pineapple you’re probably picturing in your head, while their high acidity and fibrousness make them ideally suited to canning, jamming, and becoming the sticky-sweet filling of a pineapple cake. With this in mind, the second half of our pineapple experience saw us heading back to Imagine Taitung’s kitchen workshop, where we cooked up a batch of jam. The sweet tang of the fruit’s pale-yellow flesh filled the kitchen as we chopped it into small chunks and added it to a pan with brown sugar. Finely sliced strips of green lemon rind were the third and final ingredient, and the completed concoction was ready to bottle and take home in under an hour. When we had finished there was still a little left in the pan, which was promptly scooped out in heaped spoonfuls and added to cups of red oolong – a final sweet reward for the day’s hard work.

Imagine Taitung

(饗嚮台東)

Add: No. 5, Ln. 42, Gaotai Rd., Luye Township, Taitung County

(台東縣鹿野鄉高台路42巷5號)

Tel: (089) 550-227

Website: imaginetaitung.com.tw (Chinese)

Luanshan Village Forest Experience

Much like Cidal Hunter School, Luanshan Forest Culture Museum, run by members of the Bunun tribe, wasn’t initially conceived of as being somewhere for outsiders. Instead, it was born from one man’s desire to preserve Bunun stewardship of the land from which their cultural roots drew life. Aliman Madiklan was the first man from the indigenous Luanshan (Sazasa) community to graduate from university. As a scholar and journalist of indigenous themes, he was well aware of the pressures his community faced. He’d seen many a slow disintegration as native villages sold off pockets of land to developers here and there. So, when prospectors came with plans for this patch of forest in the shadow of Mt. Dulan, he did what he knew he had to – he took out a loan and bought the right to oversee its continued existence.

That was over two decades ago, and under Aliman’s curatorship, the museum without walls has flourished into a space where Bunun culture is lived and shared. It’s both a training ground for young tribe members and a space where outsiders can come to learn more about traditional ways of living. Experiences offered here include half-day, full-day, and overnight excursions, and while the itineraries vary somewhat based on the length of your stay, there are a couple of elements that remain consistent. Groups are welcomed with a small gift of food and drinks, and before diving deeper into the tribe’s forest, everyone participates in a land ceremony to greet the tribe’s ancestral mountain spirits. (The museum asks that guests bring one pack of betel nuts and a bottle of rice wine per group as votives for use in the proceedings.)

Offerings made, groups are led on a hike through the community’s forest. Highlights include a sideways scramble through a slot canyon that’s so narrow it inspires fleeting fears of getting jammed, and an encounter with an ancient grove of “walking trees”. Ficus benjamina, or the weeping fig, is a strange beast in that it grows by colonizing other trees and then sending out trailing aerial roots. When these flimsy roots find purchase they delve deep into the ground, gradually thickening until they become strong and sturdy enough to support more branches. Over time, this leads to the impression that the trees are moving, creeping stealthily through the forest when there’s no one there to watch. The walking trees here at Luanshan Forest Culture Museum are thought to be as old as 500 years, and visitors get to know them intimately as they scramble up and between their vine-like roots.

The museum prides itself on being a bastion of traditional culture, and as such it is operated without electricity. All guests are encouraged to embrace this by turning their phones off (or at the very least, leaving them on silent), and those who choose to linger longer are treated to a mountain feast cooked using entirely traditional methods.

Luanshan Forest Culture Museum

(鸞山森林文化博物館)

Add: No. 21, Luanshan Rd., Luanshan Village, Yanping Township, Taitung County

(台東縣延平鄉鸞山村鸞山路21號)

Tel: 0911-154-806

Website: www.forestculturemuseum.com.tw (Chinese)

About the author