Indigenous Homeland Mountain Fastness

TEXT | RICK CHARETTE

PHOTOS | VISION

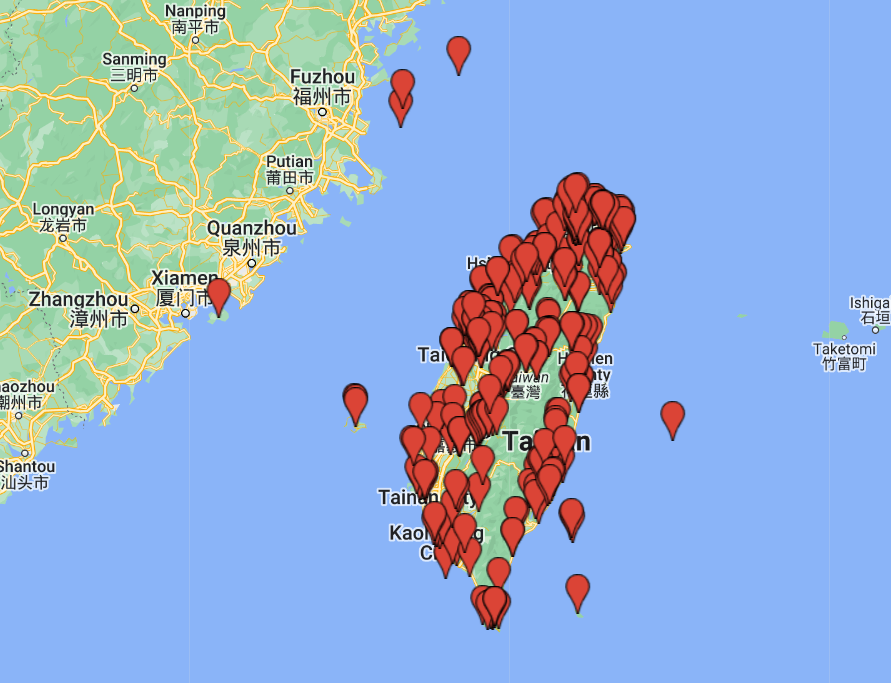

Pingtung County has a string of townships running north to south in the rugged mountain area on its eastern side in which the sparse population is overwhelmingly indigenous. Taking up the county’s northeast region are Wutai, Majia, and Sandimen townships, which receive tourist visitors in significant numbers. The native folk here, especially the younger generation, are dedicatedly striving to protect and bloom tribal traditions. They have created an enticing array of tourism-oriented attractions, concentrated in/around the dramatically located tribal villages, that showcase iconic cultural elements and their beloved homeland geography. Accessibility is convenient, with high-quality roadways, transport connections, and native-theme homestay accommodations. Below is a select list of traveler favorites.

Wutai

This township, home to people of the Rukai tribe, is the deepest and highest township in the mountains. It’s reached through Sandimen via Provincial Highway 24, which presents spectacular high-peak vistas around every turn.

Yanban (Slate) Lane, located atop mountainside-hugging, tiered Wutai Village, is the township’s best-known attraction. Stretching 500m, it’s paved with large slate slabs and lined with traditional slate-stone buildings. On the façades you’ll see symbols proclaiming the owner’s social status: elite member of the tribal nobility (a hundred-pacer viper), regular civilian, elder, hunter. Note the low entrances, which in times now gone facilitated defense and today still ensures a gesture of respect from arriving guests, who must bow heads on entry.

Wutai Presbyterian Church, close to Yanban Lane, is a castle-like structure primarily built of stone that stands high above other surrounding village buildings. Christian missionaries came to the area in the 1960s, bringing much-needed resources. The church was built by a famed indigenous artist in 1966. The exterior and interior artistry features numerous icons, powerfully combining Christian and traditional Rukai motifs. Outside, a towering warrior-chief sculpture, church bell in hand, calls the faithful to prayer. Inside, the Virgin Mary wears a traditional Rukai gown.

The Rukai Culture Museum (entry fee) is located further down from Yanban Lane and the church, before a large round plaza, used for public celebrations. From the plaza you can look straight out into the deep Ailiao River valley. The three-story museum building has a stone façade ornately bedecked with Rukai totems, among them the sacred hundred-pacer viper. Inside, the info-rich displays (Chinese) explain how slate homes and other structures such as guard towers are built – with precision miniature mock-ups of individual Wutai Township homes presented. The exhibits show impressively wide-ranging stylistic variations. Visitors can also learn about the deep symbolism of traditional tribal beadwork and the crafting/utilization of traditional fish and hunting traps.

Majia

The Ailiao River spills out of the low mountains onto the Pingtung Plain through a deep-gorge mouth seen from far off on your flatlands approach from the west, plateaus on either side. Sandimen Township takes up the low-mountain area to the north, Majia Township to the south. The inhabitants here are primarily from the Paiwan tribe. The cultures and traditions of the Paiwan and Rukai are intimately connected, and for a long period anthropologists grouped them together.

On the just-mentioned south-side plateau is the acclaimed Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Park (entry fee), among the world’s largest indigenous-theme parks. The entertainments are profuse: replicas of traditional Taiwan indigenous architecture, robust song-and-dance performances, a museum dedicated to Taiwan tribes’ rich-symbolism sculptural artistry, indigenous handicrafts DIY workshops, a hiking trail to a park overlook, and fresh-cooked native foods with exotic mountain-sourced ingredients. Note that English-language tours are available for large groups/families.

Close by the park is the young and dynamic village of Rinari, looking off the plateau’s southwest edge, with views of far-off central Kaohsiung’s skyscrapers on clear days. The residents are from three high-mountain Paiwan/Rukai villages devastated in the infamous 2009 Typhoon Morakot. The harmoniously aesthetic abodes, incongruously, are European-style A-frame and twin homes, each façade adorned with Paiwan artwork identifying the resident clan, each home beautified further with a traditional Paiwan/Rukai-style “living room” patio with welcoming low slate-slab fencing and seating. The tourist-friendly village offers a variety of enticing indigenous-theme experiences and craft-retail opportunities.

The serene cheer of immersion in Mother Nature awaits in the Liangshan Recreation Area, taking up a 2.5km low-mountain valley south of Rinari off County Highway 185. The valley’s lower section has such family-oriented facilities as a whimsical “Hobbiton village,” kid-play facilities, and goat enclosure. The signature enticement, however, is the 1.5km Liangshan Trail, which elevates you up one side of an ever-tightening, heavily forested gorge, walls ever higher, to the isolated, multi-tiered Liangshan Waterfall at the gorge’s cul-de-sac.

Sandimen

The largest Sandimen Township village is Sandi, atop the north-side plateau at the Ailiao River gorge debouche. Most outsiders simply call it Sandimen; its native Paiwan name is Timur/Tjimur.

Walk the gorge below toward Majia’s aforementioned cultural park on the monumental Shanchuan Glass Suspension Bridge, which soars 45m above the river. This is one of Taiwan’s longest suspension bridges (262m), built to replace a Sandimen/Majia-connecting structure savaged in Typhoon Morakot, which hit this region particularly hard. The Paiwan famously excel at glass-bead art, and this aesthetically inspired new structure is bejeweled with countless beads individually crafted with unique designs and color schemes by local tribal members, each expressing particular symbolic meaning.

Sandi is heavy with tourism draws. It is home to numerous renowned Paiwan artists, with tourist-inviting studios. The Tjimur Dance Theatre is the base for an eponymous award-winning dance troupe that interprets contemporary experiences through ancient Paiwan ballads. Its Paiwan-art-themed facility is airy and convivial, and includes a popular café. The Sandimen Cultural Center, designed in the style of a traditional slate house, has exhibits on assorted Paiwan themes, a performance hall, and an observatory with thumping views over the area. Outside are artworks of painted beads, clay pots, and bronze knives, a triumvirate sacred to the tribe.

Timur Art Park is a beautiful, inspiring space – on a sacred Paiwan ritual site – just above Sandi along Highway 24, which runs through the village. The spirited public artworks here are all creations by local artists, each explaining an element of traditional Paiwan culture. In the middle of the central axis is a large plaza, a mosaic sun, used for tribal rituals and celebrations; the word “timur” means the Paiwan are “people of the sun.” At one end of the axis is a soaring totem pole-style column of ancestral spirits, a symbol of masculinity and inheritance, and at the other is a giant stone cooking vessel, a symbol of female fertility and food abundance.

About the author

Rick Charette

A Canadian, Rick has been resident in Taiwan almost continually since 1988. His book, article, and other writings, on Asian and North American destinations and subjects—encompassing travel, culture, history, business/economics—have been published widely overseas and in Taiwan. He has worked with National Geographic, Michelin, APA Insight Guides, and other Western groups internationally, and with many local publishers and central/city/county government bodies in Taiwan. Rick also handles a wide range of editorial and translation (from Mandarin Chinese) projects.