Celebrating Traditional Indigenous Culture in Taroko Gorge

Text & Photos | Twelli

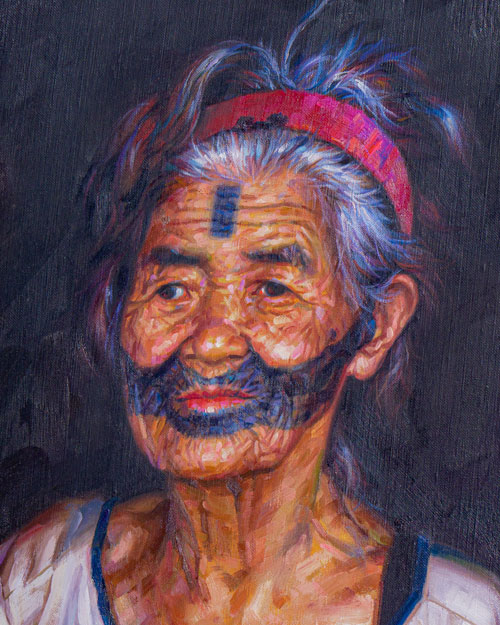

Tattoos have become very common in modern times as a widely accepted form of lasting personal statements and visual artistic expressions. While no body part seems to be off limits to tattoo artists and their regular customers, many tattoo lovers will, however, stop short of using their faces as canvas.

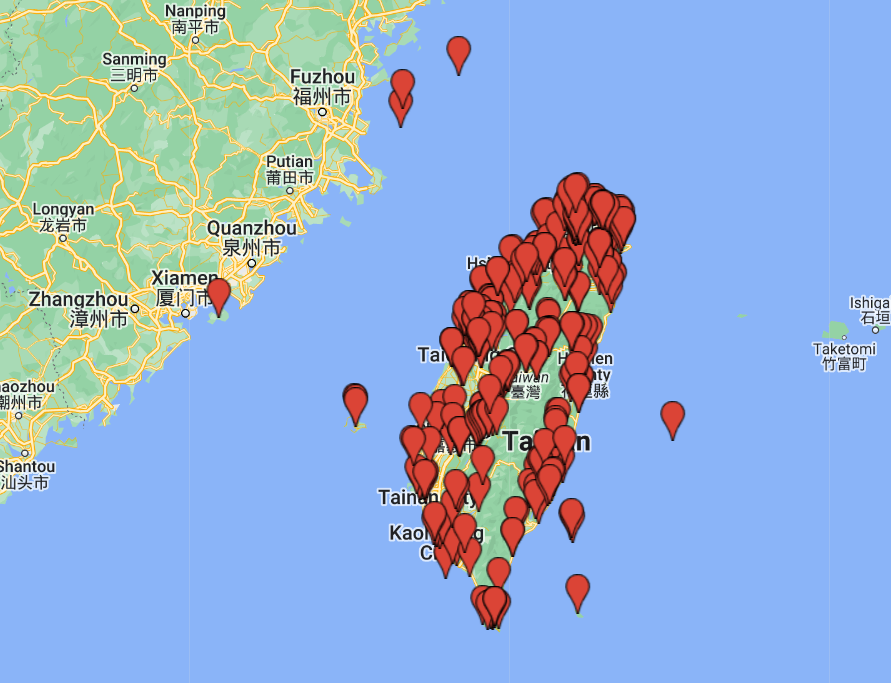

Facial tattoos, called wenmian in Mandarin Chinese, used to be widespread among Austronesian peoples, including the Maori of New Zealand, and tribes in Southeast Asia, including the Dai people of Thailand. In Taiwan, the Atayal, Truku, Sediq, and Saisiyat (with the help of the Atayal) practiced facial tattooing in the past (men with simple tattoos on forehead and chin, women with tattoos on forehead and across the cheeks/around the mouth). The custom was banned by Taiwan’s Japanese colonial rulers in 1913, and people could only continue with the practice in remote mountain areas, risking being arrested and punished.

In 2016, the Ministry of Culture honored six indigenous elders with facial tattoos as the last preservers of this art form from the old days. The last of these was an Atayal woman, Lawa Piheg, who passed away at age 97 in 2019, and a Sediq woman, Ipay Wilang, who passed away at age 100 this June. With no one from the elder generation left as living preservers of wenmian, it’s now up to younger folks to continue the tradition.

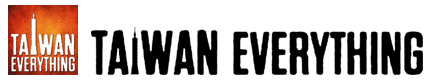

In 2011, a “Passing on Facial Tattooing” event celebrating this indigenous tradition was held at Taroko Village Hotel (www.tarokovillage.com), located inside the Taroko Gorge. Hotel manager Zheng Ming-gang (aka “Village Chief”), who has been running the hotel since 2003 and has been very active in supporting the local indigenous communities, invited some of the above-mentioned elder tribe members to honor them and encourage the younger generations to continue the tradition.

On September 25th this year the hotel organized a follow-up event. Invited this time were younger tribe members who have had their faces tattooed in recent years. Hotel staff (all Truku) first put up an entertaining acting performance telling the story of traditional facial tattooing, explaining that in order to receive a tattoo young men had to successfully learn hunting and young women how to weave.

Atayal, Sediq, and Truku from different parts of Taiwan then shared their touching stories of how they decided to get tattooed and how friends, families, and strangers reacted to their new permanently changed facial appearances. It was an emotional, meaningful, and joyful event for all participants, concluded with a grand traditional-style indigenous-fare feast in the hotel’s restaurant.

Many misconceptions about facial tattoos remain, both outside and within indigenous communities. Facial tattoos, for example, are not a sign of a headhunter, like some might still believe, and not everyone can get such a tattoo either; a traditional facial tattoo requires certain qualifications and the permission of tribal elders – and the spirits. This event showed that, for now, the practice of facial tattooing remains alive. Being a strong statement of pride in and identification with indigenous roots, and a symbol of connection with the ancestors and the spirit of one’s tribe, the practice is playing a key element in efforts to preserve traditional indigenous culture in Taiwan.