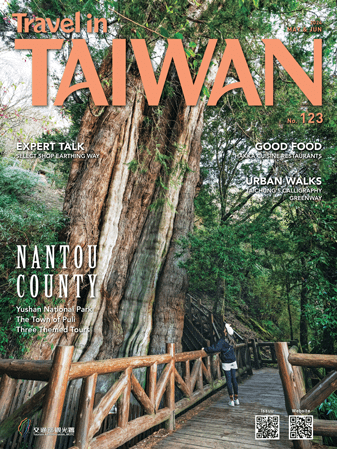

Natural Splendor, Vibrant Culture, and Superb Tsou Cuisine Await Travelers When Visiting Southern Alishan

TEXT / AMI BARNES

PHOTOS / ALAN WEN, VISION

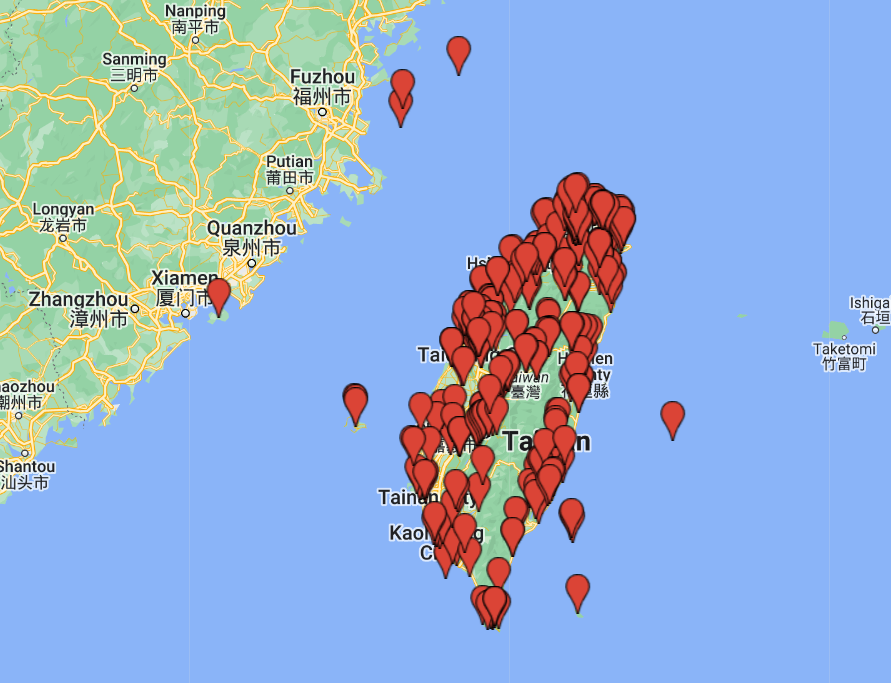

Most visitors to the Alishan National Scenic Area in southern Taiwan join the conga line of cars and tour buses snaking up Provincial Highway 18 bound for the Alishan National Forest Recreation Area or one of the many quaint mountain settlements that are surrounded by tea gardens. But for those seeking a quieter, more intimate encounter, a journey to Alishan’s southern reaches beckons.

edged at the easternmost tip of Chiayi County, Alishan Township reaches inland and upwards as far as the summit of Mt. Jade (Yushan). Its central-area attractions are well known and much loved, but the more remote and rural delights of southern Alishan remain off-radar for most visitors. This is Tsou indigenous land, and here the tribe’s culture is proudly on display. Against a backdrop of natural beauty, visitors are invited to feast on fresh and flavorful indigenous cuisine, hear what it means to belong to the Tsou tribal group, and allow the warmth and hospitality of the local people to weave a tapestry of unforgettable experiences.

Danayigu Nature Ecological Park

Turning off the arterial Route 18 (Alishan Highway) onto the narrower Chiayi County Road 129 at the village of Longmei, we began our descent towards Danayigu* Nature Ecological Park. As the road wiggled and wound through lush greenery and clusters of houses, we slalomed around sunbathing dogs that just barely mustered the energy to lift their lazy heads in acknowledgment.

[*Other spellings you might encounter: Danaiku, Danayiku, Tanaiku, Tanayiku]

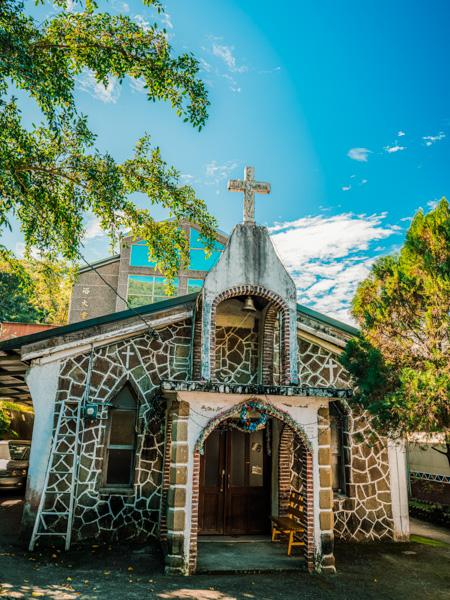

The journey takes you through the spread-out neighborhoods of Shanmei village (Saviki in the Tsou tongue). It’s one of three Tsou villages in the southern Alishan region and one of just seven in total. Here, the Tsou’s distinctive traditional black, red, and royal blue triangular artwork adorns the police station, and tucked away down short lanes, you’ll find community hubs in the form of Shanmei Presbyterian Church and the village’s tribal classroom. Around twenty minutes after turning onto the 129, we were driving across Shanmei Bridge high above the boulder-strewn Zengwen River, with the steep span of Fumei Suspension Bridge running parallel to us a bit further downstream.

Just beyond, an archway and murals depicting Tsou legends and scenes from traditional daily life mark the entrance to Danayigu Nature Ecological Park, and when we got out of our car, we were greeted by the distant sounds of the river and the riotous chatter of a nearby flock of black bulbuls. Fish motifs abound, and a laid-back unhurriedness seemed to be in the air.

There’s good reason for the prevalence of fish in the park’s artwork. The nature reserve’s very existence as a tourist attraction is thanks to the humble Taiwan shoveljaw carp. The local Tsou long used the river system’s bounty as a source of fresh food, with each family unit within the tribe allocated a stretch of land along the banks of the river and the Danayigu River (a tributary of Zengwen River) where they could catch fish, and any incursion into another family’s patch requiring the uninvited visitors to share a portion of their catch as a show of goodwill. This division of resources – when combined with low-impact methods of night fishing with prong-tipped spears and flaming torches – meant the local waterways could comfortably sustain the villagers.

However, major changes in and around the greater Alishan area, including the building of the Zengwen Reservoir (completed in 1973), the construction of the Alishan Highway (opened in 1982), the widespread planting of tea plantations, and the introduction of destructive fishing methods such as mass poisoning and electrofishing, meant that fish stocks plummeted. Village elders were alarmed, and discussions to improve the situation led to the decision in 1989 to create an ecological park in the Danayigu valley. As part of the ensuing eco-preservation efforts, families had to relinquish their birthright to riverside plots and the land was turned into a communal resource. Unsustainable methods of fishing were outlawed, and villagers were enlisted to patrol the river to ensure that the prohibition was enforced. These measures successfully reversed the decline in fish populations, and the villagers turned to eco-tourism as a way to support the community while also preserving their home area’s natural gifts.

At the innermost reaches of the park, visitors can see the happy benefactors of this conservation effort in several fish-viewing areas. Upstream, the lithe bodies of young carp churn the water near the shore, packed so tight in some spots that it almost seems there’s no room for water. And if you look down from the spectacular 228m-long Danayigu Suspension Bridge, you can see diamond-bright flashes of larger fish nipping algae from rocks in the deeper pools. At the far (north) end of the bridge, a lookout tower decorated with the cat-like face of a mountain scops owl glares at approaching walkers, and just beyond that, you can find the start of the Limei Trail, which climbs to Lijia, Alishan’s most remote Tsou village. It’s a steep trail, not for the faint of heart, that is usually only taken by experienced hikers.

Danayigu Nature Ecological Park

(達娜伊谷自然生態公園)

Tel: (05) 251-3246

Add: No. 51, Neighborhood 3, Alishan Township, Chiayi County

(嘉義縣阿里山鄉3鄰51號)

Website: alishan.welcometw.com/tanayiku (Chinese)

Hours: 8am~5pm (closed on Wednesday)

Admission: NT$150

Tsou Culture

Aside from celebrating their home’s natural beauty, Shanmei villagers make sure that visitors to Danayigu Nature Ecological Park have ample opportunities to learn about the Tsou themselves.

Close to the carpark, you’ll find an open-sided hall where there are daily performances of traditional dances blended in with a potted history of Shanmei village and an introduction to some of the customs and practices of the Tsou. The performances are well-rehearsed but not polished to excess. On the day we went, there was an endearing microphone malfunction, which resulted in the whole audience being treated to a chuckle-inducing backstage expletive before our nervous host appeared, apologetically letting us know it was her first time in the role.

After the 30-minute show, we were introduced by our guide, Yiusungu, and a village elder to a traditional Tsou hut. To add to the authenticity, a fire burned in the center of the dwelling, bounded by age-blackened stones, and smoke drifted up towards the thatched roof. Strict rules govern the usage of each quadrant of this type of abode, with the accouterments of men’s and women’s work placed in opposing corners and a large communal bed taking up another. We were shown handmade tools associated with the tasks of daily life – many of them fashioned from bamboo, rattan, or leather. We were told that these days, it’s mostly just the elders who possess the knowledge and skills required to construct dwellings or forge tools using traditional means, but the tribal villages have classrooms where the techniques are being passed on to the next generation.

The cultural show and demonstration structure both offer an insight into a traditional way of life that is part preserved, part practiced, but the most meaningful element of the experience for me was being shown around the site by a young man living in the modern world as a member of the Tsou. Yiusungu was a warm and engaging guide who openly shared interesting insights into his life experiences and brought our attention to things that we wouldn’t necessarily have thought to ask about.

He described the considerations involved in becoming a shaman (a calling that is open to all Tsou tribespeople, regardless of gender), showed where Typhoon Morakot wreaked its havoc on the park in 2009, and, with a grin, threw shade on another of the 16 officially recognized indigenous groups in Taiwan. As we walked down a path lined with various plants, he explained that in contrast to the Tsou’s traditionally protein-heavy diet, the Amis consume a greater variety of plants. This fact apparently gave rise to an old Tsou joke that you can tell when a trail has been walked by a member of the Amis tribe because the foliage to either side will have been stripped bare.

Visiting this place, there’s a clear sense that the idea of being an extended family runs strong in the Tsou. Indeed, a communal endeavor such as Danayigu Nature Ecological Park could surely not exist without a deep commitment to – and belief in – the community. No doubt, the fact that the Tsou have been able to preserve their language (Yiusungu and many of the other residents of Shanmei grew up speaking it) and festivals have both contributed to preservation of the community spirit. And apparently, it’s a common practice among the villagers to try any which way they can to entice fellow tribe members who are living outside the community to come home.

Lunch in the River

A highlight of any trip to one of the Tsou’s village communities is the opportunity to indulge in some freshly cooked indigenous fare. There are a number of eateries within the park boundaries, as well as a small stall selling locally grown seasonal produce like Alishan limes, chayote melons, and tamarillos.

Barbecued meats feature prominently on every menu, and the heady aroma of cooking meat and wood smoke was enough to make me salivate despite three decades of vegetarianism. The barbecue set-up itself at the eatery we chose is something of a showy scene-stealer for those unacquainted with Taiwan’s indigenous-style grills. An oversized suspended circular grill – well over a meter in diameter – hangs above a fire pit, and is spun, raised, or brought closer to the flames as the chef desires. The grill is loaded with treats such as pork belly, sausages, bamboo tube rice, fat sweet potatoes, and salted fish, which are infused with a rich, smoky flavor as they cook.

Our visit was on a weekday, when the park has fewer visitors, so the sausages and pork belly for our lunch sets were grilled to order on a smaller barbecue by a tattooed chef as tunes from Paiwan-tribe pop princess Abao blasted through the restaurant’s speakers. The place we ate in is sheltered from the sky, but save for an enclosed kitchen, it’s open-sided, allowing the wood smoke to drift languorously up through shafts of sunlight. The tables and benches are fashioned from bamboo, and when our meals arrived, they were appealingly presented on cut squares of banana leaf. We ate the Hunter’s Lunch set – a veritable feast, with many small dishes containing all sorts of tasty treats. For the carnivores among us, the centerpiece of the meal was the aforementioned barbecued meats accompanied by raw garlic and onions, while the vegetarian option featured an omelet in place of meat. Rounding off the set were generous servings of spicy julienned green papaya salad, tender pumpkin, impossibly sweet sweet potato, ripe red dragon fruit, and crispy battered black-jack leaves – black-jack is a cousin of the common daisy and can be seen growing along the park’s riverbanks.

For anyone visiting in the warmer months (April to October), the eatery offers an unmissable dining experience: the chance to enjoy a meal like the one detailed above while in the cool waters of the Danayigu River, your feast floating on the surface. The “Floating Restaurant Set Tour” is an almost full-day package that includes a detailed introduction to the Tsou way of life, a DIY session, and a leisurely lunch surrounded by the fish in the large pool below Danayigu Suspension Bridge.

Of course, you’re free to choose whether to paddle or opt for full immersion, but if you visit in the height of Taiwan’s summer, I guarantee you’ll want to be up to your neck in cool water. The park provides guests who need them with a life jacket, but that aside, you’re free to enter the water wearing whatever you feel most comfortable in – just remember to pack a towel and a change of clothes if you don’t want to spend the drive home in soggy shorts. And my personal advice would be to take something loose but long-sleeved, and a hat that covers your neck, because the strength of the summer sun up here is formidable, even on cloudy days.

The tour has to be booked ahead of time through the Alishan National Scenic Area’s tour and activity site at alishan.welcometw.com/Tanayiku (Chinese).

Handicraft DIY

In addition to fish viewing and cultural experiences, visitors to Danayigu Nature Ecological Park are also able to get hands-on with a range of DIY crafting experiences. The craft classes – which have to be booked ahead of time – allow guests to try their hand at a range of traditional skills such as leatherworking, food preparation, and woodwork.

Tsou traditional clothing incorporates more leather than the clothing of other indigenous peoples in Taiwan. This is especially true for men, whose traditional attire consists of chaps made from the hides of muntjac deer. Also common are leather shawls and caps made from deerskin and adorned with feathers. (Women’s outfits, meanwhile, tend to be made from cotton or silk.) A Tsou legend says that the tribe learned how to tan leather when an overzealous young hunter failed to heed the advice of his elders and injured a mountain spirit in the form of a moon-eyed deer. After the hunter and his brother caught up to the wounded creature, it seized the youngster, rubbed his body back and forth over the crook of a branch to soften the skin, and instructed the older brother to return to his village and tell the tribesfolk that this was how they should work leather. When you visit the demonstration hut, keep a lookout for the work-smoothed branch lashed to one of the central poles – this is where hides would traditionally have been processed.

Thankfully for contemporary visitors, no such strength-testing work is required to partake in the leatherworking DIY activity. Instead, you’re given a couple of leather offcuts in the shape of a fish that you can decorate as you please. Yiusungu led us lightly through the process, stepping in now and then to help, but mostly leaving us to our own devices. After wetting the leather to soften it slightly, you can select from a range of small metal stamps, which are then used to hammer a pattern into the material using a mallet. Different stamps require different amounts of strength, so it’s well worth practicing on some of the little scraps first so that you can get a sense of how hard you should be hitting. Once we were satisfied with our designs, Yiusungu helped us glue the two sides of our fish together and had us shave off the excess fabric before burnishing the edges with a conical wooden tool. With that done, we were let loose on the colors – just the smallest drop of dye is needed to impart a vibrant tone to the leather’s surface. The project is completed with the addition of a keychain, and voilà, you have a small keepsake of your time with the Tsou of Shanmei village to take home.

We also had a go at making our own “hunter’s packed lunches.” In the modern version, tender chunks of pork belly are wrapped in sticky rice and steamed inside the leaves of the parasol leaf tree. In the past, these portable snacks were prepared with just rice or millet and were carried by hunters on their forays into the forest. Once they’d caught something, they’d process the meat wherever they set up camp and enjoy a satisfying full meal.

As well as the above crafts, other activities offered at the park include creating your own cup from bamboo as part of the “Floating Restaurant Experience,” and having a go at making millet wine.

Nearby Attractions

Visitors staying in the area for an extended period have countless other options for how to spend their time. Even just within the southern Tsou villages, there are plenty of cultural and natural attractions to enjoy.

If you continue to follow County Road 129 southwards as it nears the border with the city of Kaohsiung, the next village you’ll arrive at is Xinmei (Niahosa in the residents’ own language). The Tsou name for this settlement means “ancient village” – a moniker that was proved very apt in 2002 when archaeologists discovered tools and a stone coffin belonging to the now-disappeared Dagubuyanu Culture that are at least 3,800 years old.

The administrative center of the village – where two churches, an assembly hall, shops, and an elementary school are all collected – sits north of Dagubuyanu Stream, which feeds into the Zengwen River. Encouraged by the success of Danayigu Nature Ecological Park, Xinmei villagers have created an ecological protection zone along the stretch of Dagubuyanu upstream from Xinmei Bridge. A pleasant one-hour walk here takes you past several fish-viewing areas as well as other scenic spots.

Keep heading south for another nine kilometers and you will arrive at the third and largest southern Tsou village: Chashan (Cayamavana). Despite the name (a literal translation of the Chinese would be “Tea Mountain”), you won’t find any tea plantations nearby. Instead, the name references another type of camellia tree that once covered the nearby mountain slopes.

Unlike Shanmei and Xinmei, whose residents are almost exclusively members of the Tsou tribe, Chashan’s population is an amalgam of Tsou, Bunun (another indigenous tribe), and Han Chinese. The village boasts several homestays and unfussy restaurants selling authentic local dishes, and is famed for its proliferation of traditional-style thatched-roof pavilions (known as “hufus”) and indigenous artwork.

The area around Chashan is also rich in natural beauty. Those who have indulged in a little too much barbecued meat might want to get some exercise in by taking a walk to one of the innumerable waterfalls dotted around the rugged terrain – plenty of which offer swimming or soaking opps. One such spot that can be reached on foot from Chashan is Jiayama Waterfall. It also happens to be located right next to the bizarre Fire and Water Source – a spring where flaming natural gas and water simultaneously spill from the earth.

Tsou Celebrations

Each year the Alishan National Scenic Area Administration, in collaboration with Alishan’s nine Tsou villages, organizes the Alishan Tsou Annual Festival, which includes the Chashan Hufu Festival, Dabang Jelly-fig Festival, Fo’na Festival, Laiji Thanksgiving Festival, Lalauya Coffee Industry Festival, Muni Music Festival, Shanmei Taiwan Shovel-jaw Carp Festival, Xinmei Tea Seed Oil Festival, and Zhulu Sharing Festival, as well as the highly popular Muni Music Festival. The music festival, held on two separate days at Veoveoana Cultural and Creative Park and Danayigu Nature Ecological Park respectively, features a line-up of indigenous performance troupes and well-known pop bands and music artists. The performers are from the Tsou tribe as well as tribes from other parts of Taiwan. Last year’s event, coinciding with the 30-year anniversary of Danayigu Nature Ecological Park, featured the Veoveoana Performing Arts Troupe (Tsou), Limei Performing Arts Troupe (Atayal, Amis), singer Shen Wen-cheng (Rukai), the bands Kanit (Rukai) and Am Band (Tsou), and singer Sangpuy Katatepan Mavaliyw (Puyuma). www.ali-nsa.net/en/explore/annual-events; www.ali-nsa.net/tsou-celebration (Chinese)

If the above introduction to southern Alishan’s allure has ignited your wanderlust, perhaps it’s time to make it your next destination of choice – this culturally rich and scenically gifted region of Taiwan has much to offer the curious traveler.

About the author