Preserving Traditional Culture in One of Taipei’s Oldest Neighborhoods

TEXT / OWAIN MCKIMM

PHOTOS / SHUN WEN YANG

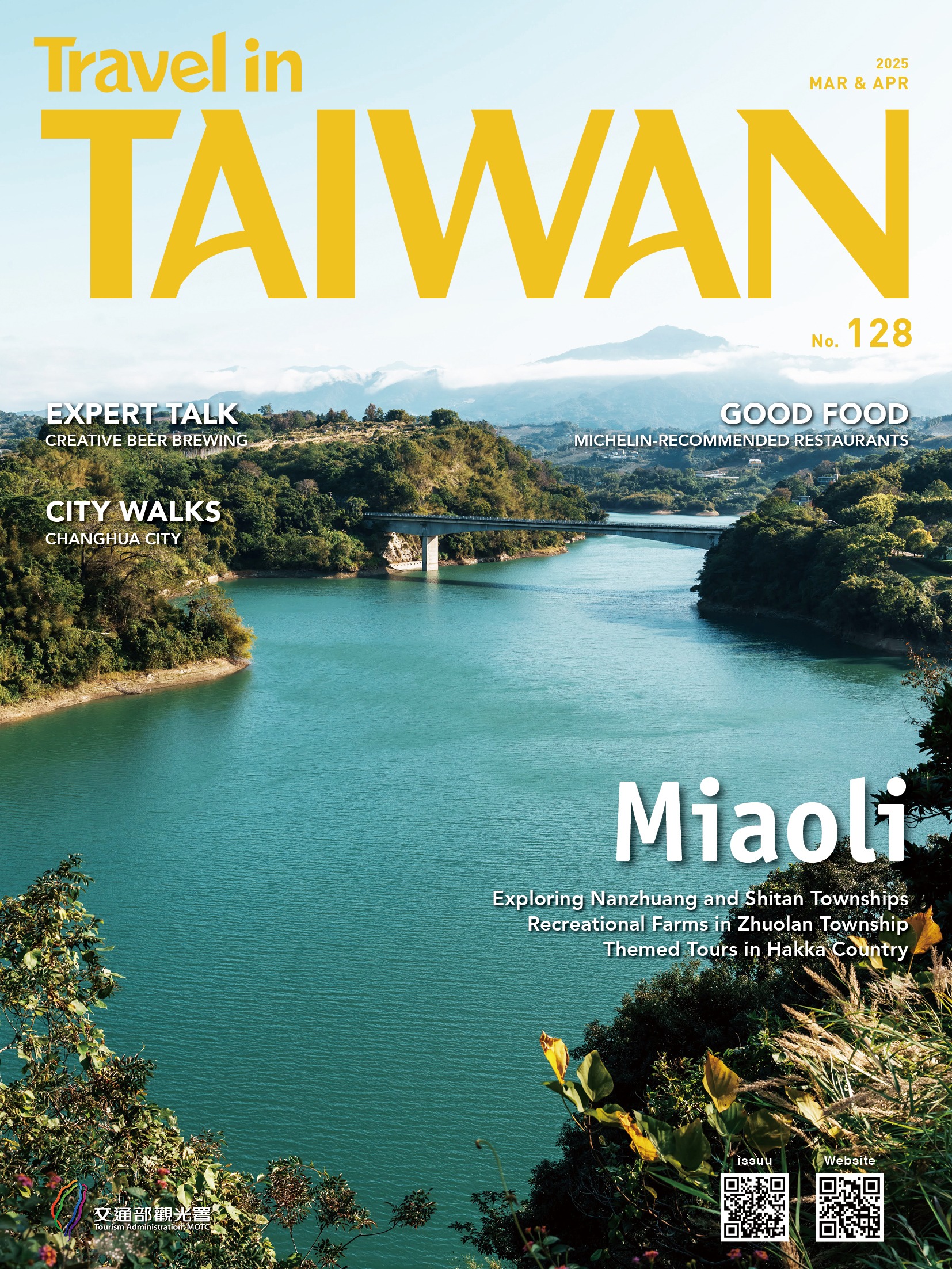

In an ever-changing city like Taipei, where the urban landscape seems constantly in flux, holding onto the past is no easy task. For Chen Jie-fu, a former news broadcaster with deep ancestral roots in Taipei’s Datong District, however, history – whether in the form of old buildings, arts and crafts, ritual, or cuisine – is something that is certainly worth fighting for. And where better to make this stand than in Dadaocheng, one of Taipei’s best-preserved historic neighborhoods.

Tongan Family Selection

We meet Chen on the second floor of No. 121, Dihua Street, a heritage residence that Chen now runs as a teahouse. “The layout is all original,” he says, gesturing to the walls of red-stained cypress that divide the space into semi-private seating areas. “These used to be the family’s living quarters. Downstairs used to be their storefront, where they sold rice and oil.”

Sunlight streams through the wood-framed windows that look out onto bustling Dihua Street, the commercial spine of the Dadaocheng neighborhood, which experienced a huge economic boom in the late 19th century as hub for exporting Taiwan’s famous oolong teas to the world. Today, it is the core of one of the city’s best-preserved areas, with many buildings – their architecture a curious mix of European and East Asian styles – well over a hundred years old.

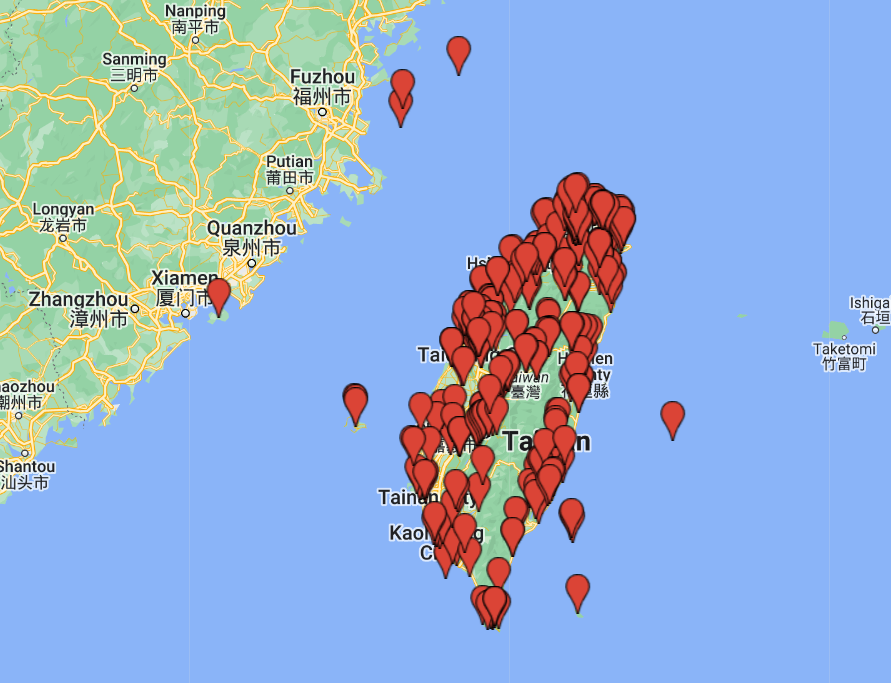

“This year marks 170 years since Dadaocheng’s founding,” Chen says. During the Qing dynasty, he explains, many settlers from China’s Fujian Province set up homes on the eastern bank of the Xindian River, in the area that is today known as Wanhua District. However, in 1853, a conflict broke out between tradespeople from the Fujian districts of Tongan and Sanyi. Losing the conflict, those from Tongan fled to the village of Dalongdong further north on the eastern bank of the Tamsui River, where many fellow immigrants from Tongan lived, and subsequently settled just south of Dalongdong in what is now Dadaocheng. (Today, Dalongdong and Dadaocheng together make up Datong District.)

Chen’s ancestors moved from Tongan to Taiwan nine generations ago, settling eventually in Dalongdong. His family history is deeply intertwined with the area. His great-grandfather, for example, donated the land on which the area’s Confucius Temple is built, and his ancestral home – known as the Teacher’s Mansion – is a listed historic site currently undergoing renovation in collaboration with the central government. It is in deference to these ancestors from Tongan, and their culture, that he named his enterprise Tongan Le – “Tongan Happiness.”

Moving towards the back of the teahouse, Chen shows us the atrium, an architectural element common among the shops of Dihua Street and one that speaks to the cultural values of those who built them. “In traditional Chinese architecture, the atrium is very important because it allows in air, water, and light. Water in particular is symbolic of wealth, so having an area inside the house that collects water is very desirable.” Beyond the atrium is a rear section that once served as a warehouse, but which now houses the building’s owners.

Chen draws my attention to the architectural style of the old warehouse – red brick with a tiled swallowtail roof. “You see how different it is to the shop’s front? During the Japanese colonial era, the Japanese were obsessed with modernization and Westernization. So they encouraged the building of these Baroque-style façades you can still see on Dihua Street. But behind those façades, as you move backwards along the length of the structure, the old southern Fujian style of architecture is preserved. It’s what makes these shophouses so interesting.”

Chen laments the fact that today many young Taiwanese seem more interested in buildings from the Japanese era, many of which have in recent years been turned into the core attractions of cultural parks, than these older houses. “I think it’s important to remember that these houses, which have a history dating back to before the Japanese time, have some important stories to tell too. Taiwanese should know that their ancestors from Fujian were ingenious, hard-working people.”

For Chen, who spent many years doing business in China and seeing first-hand the result of the Cultural Revolution, an attempt to erase all traces of traditional culture, it is important that the same thing not happen, out of neglect, in Taiwan. “As well as preserving these old buildings and their stories, we also want to draw more attention to traditional arts, crafts, and music – and so we use this teahouse as a space for craft workshops and lectures, as well as performances with instruments such as the erhu and guqin.”

Tongan Family Restaurant

Another way Chen is shining a light on southern Fujianese culture is through cuisine, which he strives to do in another of his ventures, a restaurant, situated a short walk up Dihua Street at No. 242. Inside, the restaurant is simply decorated, though with none of the exposed brickwork and beams that are on show at the teahouse (this building was previously rebuilt and therefore lacks the original construction work). However, the walls are decorated with intriguing curios from Chen’s own family collection, including, most obviously, items of traditional clothing spread out and framed to show off their shape and splendor.

Seated in this building’s atrium and eager to taste what’s on offer, we tuck into tender braised meatballs with Chinese cabbage, a mountain of stuffed deviled clams, chicken stewed with chestnuts, and a creamy glutinous-rice congee, sprinkled with goji berries, in which bobs a succulent chicken drumstick. Although certainly delicious, what makes these dishes special is the connection they form with the past. Chen, like most Taiwanese, maintains the practice of ancestor worship, as part of which incense is burned alongside offerings of food. “It’s important that the ancestors are offered food they enjoy,” Chen says. “In my family’s genealogy record, not only the names of the ancestors are recorded but also their favorite dishes. The dishes served in this restaurant are some of those favorites.” And indeed, with this knowledge in mind, eating these historical dishes in an area so steeped in history makes the meal a surprisingly poignant experience.

Chen, as a former journalist, clearly knows the importance of a good story – something he aims to take forward into his next project, a documentary series about some of Taipei’s old residences with histories dating back to Taiwan’s Qing era. Indeed, whether it be through food, architecture, crafts, music, or simply good storytelling, Chen is committed to giving voice to the culture of his ancestors, ensuring its influence and significance is not readily forgotten.

Tongan Family Selection/Tongan Family Restaurant

(同安樂選品/同安樂餐廳)

Add: No. 121/242, Sec. 1, Dihua St., Datong District, Taipei City

(台北市大同區迪化街一段121/242號)

Website: tonganness.com (Chinese)

Facebook: www.facebook.com/Taipeiness

About the author