Visiting the Amis Village of Fakong in Fengbin Township

Text & Photos | Twelli

In recent years, numerous indigenous communities in Taiwan have started offering tours and workshops, providing visitors with a glimpse into traditional tribal life. These experiences often go beyond the typical tourist fare of singing and dancing shows or souvenir shopping.

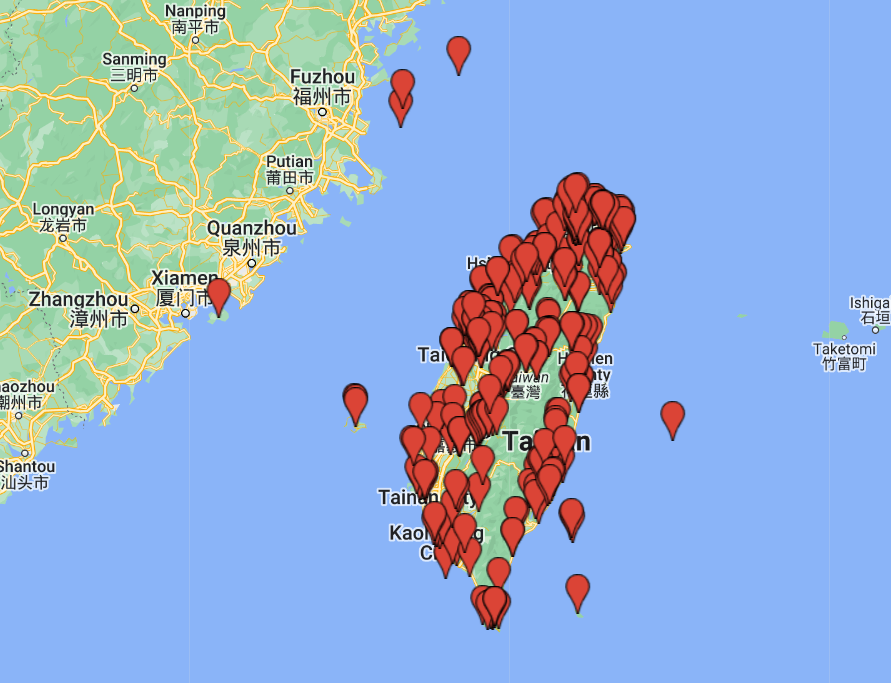

We have visited numerous buluo (the Chinese term usually used for “indigenous village/community/sub-tribe) throughout Taiwan over the years, and have noticed a trend toward high-quality experiences that offer visitors a meaningful and immersive introduction to the lives, traditions, and cultures of the various indigenous peoples.

Here are a few recent posts of visits to different indigenous communities:

Among Ancient Giants — Smangus | Hsinchu County

A Day-Trip to Danayigu | Nantou County

Trip to Tuban | Taitung County

Eastern Taiwan: Adventure Playground | Hualien and Taitung counties

PINGTUNG Indigenous Villages | Pingtung County

The Last Facial TATOOS? | Hualien County

Seeking Harmony with NATURE | Hualien and Taitung counties

I recently had the opportunity to visit two Amis communities in southern Hualien County: Fakong in Fengbin Township and Kiwit in Ruisui Township. We had a fantastic time meeting friendly locals, enjoying delicious indigenous cuisine, taking in stunning scenery, and learning about life in southern Hualien. In this post, we’ll explore the village of Fakong. You can read about Kiwit here.

Fakong

The indigenous village of Fakong in Fengbin Township is located near the intersection of Provincial Highway 11 and Provincial Highway 11A, which connects the town of Guangfu in the East Rift Valley with the coast. Known in Mandarin as Maogong (the Chinese character mao (貓) means “cat”) the village name has no connection to cats, despite the presence of a few. Fakong actually refers to a type of wild plant, commonly known as poison bulb or spider lily (Crinum asiaticum), that used to grow abundantly in the village and its surrounding areas. The Amis name for this plant is fakong.

Prior to this trip, I had never heard of Fakong, despite passing by it several times while driving along the coastal highway. If you’re traveling up or down the coast, perhaps by bicycle, you can easily stop and explore this village. Just a few hundred meters from the highway, you’ll find a watchtower, a common feature in Taiwanese indigenous villages. The community center of the buluo is located near this tower.

At the community center, we met Komay, our local guide for the day. A young man who returned to Fakong four years ago after spending most of his life in the big city, Taipei, Komay’s decision to leave the city was a significant one. For young tribe members, choosing to stay in or return to the buluo means sacrificing a wider range of career opportunities, a more modern and exciting lifestyle, and the conveniences of urban living. Living in the village are mostly elders and their grandchildren and the pace of life is much slower. Additionally, the traditional ways of life in Pangcah society can impose significant pressures and obligations on younger generations, especially given the traditional hierarchical structure.

Despite the challenges, there are also significant benefits to living in the tribal homeland. Fakong offers a peaceful and quiet environment, fresh air, and breathtaking mountain views. Many indigenous communities around Taiwan have witnessed a return of younger tribe members who are launching projects to revitalize their communities and attract visitors.

In recent years, we’ve had the opportunity to learn about many of these projects and have been deeply impressed by the youthful enthusiasm, openness, and passion for introducing outsiders to indigenous life. Komay, who speaks English fluently, introduced himself and his people as Pangcah. In Mandarin Chinese, the tribe is called 阿美族, which is romanized as “Amis.” However, the tribe members prefer to be called Pangcah. The “P” in “Pangcah” is a voiced bilabial stop, similar to a “B,” and the “k” in “Fakong” sounds more like a “g.” Komay pointed to a nearby fakong plant and explained that the village was named after this toxic plant, which was abundant in the area when early settlers made this area their home. The tribe members admired the plant’s resilience, as it could withstand even the strongest floods from the nearby river.

He then pointed to a massive slab of wood with the engravings of the names of former village chieftains.

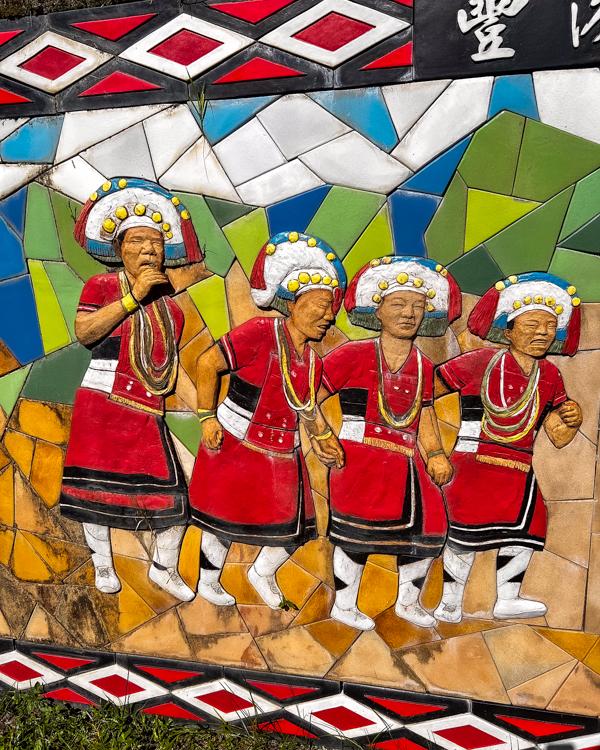

In the past, the community center served as a post where members of the tribe in charge of guarding the village would be stationed at all times. Today, however, it is primarily a venue for leisure activities and important annual happenings, the most important of which is the tribe’s annual festival. By outsiders often simply called harvest festival, in the Pangcah language it is known as Ilisin, which has the meaning of “taboo.” The festival is held after the main season for growing rice (February-June/July) and catching fish in the ocean (March-July; coinciding with the Black Current [Kuroshio], which brings flying fish that in turn attracts bigger fish such as tuna, marlin, and mahi mahi) is over. The exact dates, in July or August, of the festival will be decided by mediums communicating with the spirits, but it will be around the time of the full moon.

The festival begins at the community center, where ancestral spirits, including the chieftains whose names are engraved on the wooden slab, are invited to join. For the first three days of the six-day festival, sacred ceremonies are held at the center, which, during this time, is closed to visitors. The chieftain ascends the watchtower and calls the men of the tribe together for the ceremony. During the final three days, a variety of group dancing and singing performances take place on a large field near the river, and visitors are welcome to participate.

Next, we learned about the villagers’ traditional livelihoods, which included fishing in the nearby Fakong River. Interestingly, their fishing techniques involved using toxic plants to stun the fish and creating shallow sections in the river to be able to catch fish, crabs, and shrimp more easily.

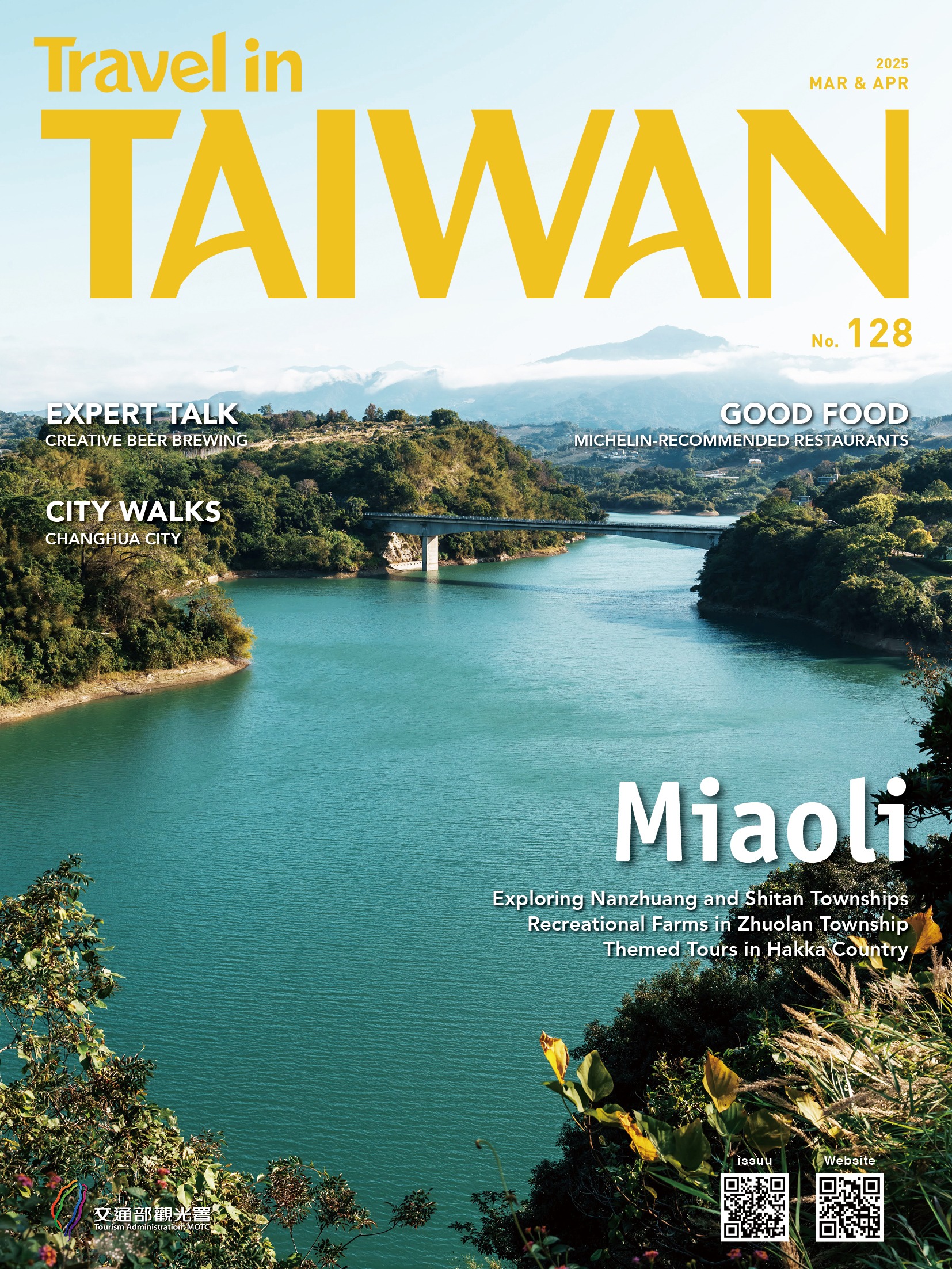

The river is located near the community center, and from a nearby bridge, you can enjoy enchanting views of the surrounding verdant hills. In the distance, you will see a mountain that is sacred to the tribe, known as Cilangasan (Mt. Qilaiya or Mt. Baliwan in Mandarin). At 926 meters, it’s the highest peak in the northern part of the Coastal Mountain Range and is also one of Taiwan’s “100 Small Peaks.” Before the Ilisin Festival, men of the village spend a night on this mountain, and upon their return they will bring with them the mountain spirits. Festival rituals also involve the spirits of the sea and the river. One ritual, on the first day, involves fishing in the river and then throwing the caught fish, mixed with glutinous rice and pig liver, into the ocean to seek protection from the sea spirits.

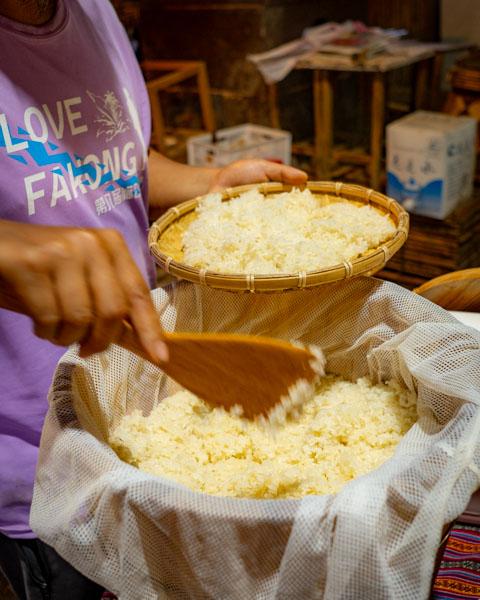

After learning about the sacred mountain and the rituals of the Ilisin Festival, we visited the riverside park, which serves as the main festival ground. Inside a traditional hut there, visitors can participate in a fun DIY activity: making glutinous-rice wine, known as kani’ in Pangcah. This drink is not only an important beverage for special occasions but also plays a crucial role in communicating with the spirits, such as during the Ilisin Festival. While I initially believed that millet wine was more common in indigenous communities, I learned that glutinous rice is the main ingredient in Fakong. Our guide explained that the Pangcah no longer grow millet, which is more prevalent in mountain tribes like the Atayal and Bunun.

The primary activity for visitors is mixing the rice with a fermentation agent or distiller’s yeast (jiuqu in Mandarin) made from locally sourced wild herbs. The number of herbs used varies and can range from 6 to 13 depending on the village and winemaker. Traditionally, winemaking has been exclusively practiced by female tribe members, and Fakong still has over ten elderly women who specialize in this craft. The village even has a “winemaker street” lined with several private winemaking operations. One reason for these home-based operations was a government ban on private alcohol production in the 1960s, forcing winemakers to work in secret. Another reason is the numerous restrictions and taboos associated with winemaking, leading many winemakers to prefer the control and privacy of their own homes.

The visitor activity of making glutinous-rice wine is simple yet enjoyable and includes a wine-tasting session. The wine, which has a low alcohol content of 6-8%, is smooth, mellow, and slightly sweet.

The first step involves grinding the distiller’s yeast into a paste using a mortar and pestle. The steamed glutinous rice is then placed on a plate to cool. After sprinkling some water on top, the yeast and rice are mixed together. The mixture is then stored in glass jars and will be ready for consumption after being stored for several weeks.

In addition to glutinous-rice wine making, another DIY activity available at Fakong is weaving. We visited the village’s weaving workshop, where we met a skilled weaving expert grandma. On the outside wall of the studio, you can learn about the eight steps of weaving with ramie, which is primarily used for clothing.

We were shown by a village grandma a simple process for creating a bed mat. The material used is the stalks of the umbrella plant, named for its umbrella-shaped leaves. This plant can be easily found around the village.

After cutting off the stalks, the leaves are removed, and the stalks are sorted and dried in the sun for about two weeks. It’s important to avoid any contact with water (rain) during this time to prevent the stalks from spoiling.

The weaving process is quite simple. The stalks are placed in succession on a horizontal wooden block with approximately two dozen threads attached. Each thread is pulled down from the wooden block by a weight, such as a thick screw. Every other thread is pulled across the next stalk placed on the wooden block alternately until the mat is completed and ready for finishing touches.

To allow visitors to get some hands-on experience, the stalks are cut into hand-length segments and placed on a much smaller wooden block in the same manner as described above. The result is a cute coaster made from natural materials that can be finished within an hour or so.

During the DIY session, we had time to chat with the elders and also taste some snacks and drinks prepared for us, including rice topped with fermented raw pork, a Pangcah specialty. If you visit the village as part of a larger group, apart from the village tour and the DIY experiences you will also be enjoying an indigenous feast, featuring specialties, such as grilled boar and assorted wild vegetables.

Before we left Fakong, we were treated to a lovely farewell song that conveyed the message “You are welcome to come back anytime”, showing the passion and friendliness of our hosts.

We had a short, fun-filled time in Fakong. Thanks to our knowledgeable guide Komay, we learned a lot about the Pangcah people who live in southern Hualien. The next day, we visited the village of Kiwit in Ruisui Township. Read about it in the next post on this site.

For more info about indigenous village tours and experiences in eastern Taiwan, check out the Travel in Sea Style (Sea-Style Adventure) website: https://jacreative.com.tw/travelinseastyle/index-en.php

You can find more details about the Fakong experience here: https://jacreative.com.tw/travelinseastyle/project-en.php?id=4

Facebook page of the village: https://www.facebook.com/cilangasanfakong

You can book a tour here: https://newpacific1.rezio.shop/en-US/product/NGJW6G

Also, check out the offerings by MyTaiwan Tour: https://www.mytaiwantour.com/products/detail/833-coastal-beauty-%26-indigenous-weaving-day-tour-in-hualien

About the author

Twelli

Long-time resident of Taiwan, Twelli likes to go on trips around Taiwan and make videos.