Deep Mountain Valleys and Plateaus + Native Fare and Crafts

TEXT / RICK CHARETTE

PHOTOS / ALAN WEN, VISION

The most-times patient, typhoon-sometimes raging Ailiao River has carved a magnificent high-wall valley deep into the central mountains. As you approach its tall, imposing mouth from the plains, can you hear it? From valley’s inner recesses come calls from native warriors standing high on mountain slopes, welcoming you to visit and know their people.

Pingtung County is home to members of the indigenous Rukai and Paiwan tribes, indigenous folk constituting about 7% of the approximately 800,000 total population. The tribes, which share many cultural traits, intermix in Neipu, Sandimen, and Majia townships. Neipu is a farm-predominant flatlands area east of Pingtung City. Majia and Sandimen are low-mountain areas to Neipu’s east and northeast, respectively. Wutai Township, a remote high-mountain region to Sandimen’s east, is predominantly Rukai.

The region has a splendid concentration of tourist-welcoming workshops operated by native artists and artisans, eateries where you can partake of the distinctive indigenous culinary traditions, and manifold other sites of interest showcasing the thriving local native culture.

Wutai Township

What is known as Wutai Village is a collection of settlements far up the Ailiao River valley, along wide, well-maintained Provincial Highway No. 24. The first three destinations below are in the largest and most remote enclave, also highest up a mountainside.

Yanban Lane

Yanban (Slate) Lane is at the top of this tiered settlement. Stretching 500m, it is paved with slate slabs and lined with traditional slate-stone buildings. On the façades are symbols proclaiming the social status of the owner: elite member of the tribal nobility (a hundred-pacer viper; see note in museum entry below), regular civilian, elder, hunter.

The Rukai are renowned as deft sculptors, and as well along the lane you’ll come across tribal scenes depicted in large stone reliefs and sculptures: tribal warrior heroes, wise elders with wizened faces, women engaged in ancient-way weaving… and one young hunter with wild boar on shoulder, yelling out into the valley ether – one of the above-mentioned warriors “calling out to you in welcome.”

Wutai Presbyterian Church

This place of worship, just beyond the lower end of Yanban Lane, is a church of unique beauty in one of the most majestic settings such places exist. Powerful mountains fill your photo backdrops. Deliberately, the castle-like church, built by a famed indigenous artist in 1966, is raised high above other surrounding village buildings on a base faced by massive stone blocks and seems to float just below heaven.

Complementing the traditional Christian motifs such as two sizeable sculptures of angels playing cornets on the roof are a plentitude of idiosyncratic Rukai cultural expressions. On the roof and behind the altar are two tall, thick cypress crosses. Atop a stone-block tower beside the church is a towering sculpture of a warrior-chief in ceremonial dress, church bell in hand, calling people to worship – and “calling out to you in welcome.”

Wutai Presbyterian Church (基督長老教會霧台教會)

Add: No. 76, Zhongshan Lane, Neighborhood 9, Wutai Village, Wutai Township, Pingtung County

(屏東縣霧臺鄉霧台村9鄰中山巷76號)

Tel: (08) 790-2204

Facebook: www.facebook.com/vedai.kiwkai

Rukai Culture Museum

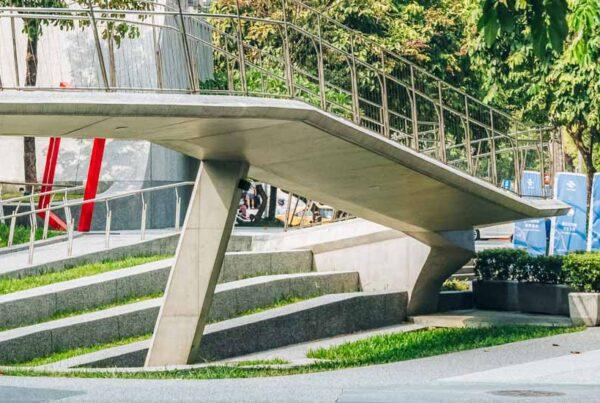

The Rukai Culture Museum (entry fee) is toward the bottom of the settlement. It stands at the rear of a large round-shaped terrace plaza that is this community’s public-gathering heart. This is one of just two large, open flat areas – the other is the sports ground of the elementary school, just uphill. The plaza is the one spot where you’re likely to sit down amidst townsfolk; Taiwan’s indigenous peoples tend to be retiring with strangers, and the locals hang out here enjoying the big shade trees and unobstructed breezes. There’s a small drinks/snacks cabin with picnic tables.

The plaza, laid with slate slabs, looks off into the vast space of the mountain valley beyond, other Rukai villages seen on the steep slopes in the distance opposite. A giant traditional-style swing is in the center, used in iconic Rukai boy-girl romancing and wedding rituals. Large statues of Rukai males and females in varied traditional attire are lined up at the plaza’s edge.

The large three-story building that the museum is housed in has a façade of flat slate stones intricately pieced together and is ornately bedecked with Rukai totems, among them the hundred-pacer viper. Traditional Rukai belief is that they are descended from this snake and that it is a guardian spirit. Inside is a treasure-house of relics and explanatory information (Chinese; audio narration also provided). Perhaps the most visually entertaining display explains the techniques used in building slate homes and other structures, with a wonderful section of miniature mock-ups of individual Wutai Township buildings, showing the surprising stylistic variation (each Rukai building is given an identifying name). Another display explains the deep symbolism of traditional tribal beadwork, for which the Rukai/Paiwan are also renowned. And another intriguing exhibit shows how traditional fish and hunting traps were created and used.

Rukai Culture Museum (魯凱文物館)

Add: No. 59, Zhongshan Lane, Neighborhood 9, Wutai Village, Wutai Township, Pingtung County

(屏東縣霧臺鄉霧台村9鄰中山巷59號)

Tel: (08) 790-2297

Hours: 8:30am ~ 12:30pm, 1pm ~ 4:30pm (closed on Mon. and Tue.)

Facebook: www.facebook.com/Ngudradrekai

Lrimumu Teke

This shop, and the one below, face each other across Provincial Highway No. 24 in a settlement just west of, and lower in elevation than, the one we’ve just visited. Collectively the two enclaves are commonly referred to as the Upper Wutai Community. These two food-and-beverage operations are popular stopping-off joints for tourists exploring the region.

As you approach Lrimumu Teke, it’s clear what the signature offering is at this open-front vendor – visuals of delectable donuts abound. The specialty is deep-fried-before-you doughnuts, topped with powdered sugar, made with millet. Foxtail millet is a staple crop for the Rukai and other Taiwan tribes, used to make wine and in foods such as cinavu (meat mixed with fermented millet and powdered taro wrapped in leaves and cooked), and celebrated at their renowned annual millet harvest festival.

Lrimumu Teke (莉姆姆的歌)

Add: No. 23, Shenshan Lane, Wutai Village, Wutai Township, Pingtung County

(屏東縣霧台鄉霧台村神山巷23號)

Tel: (08) 799-7171

Hours: 1pm ~ 6pm (from 9am on Sat. and Sun., closed on Mon.)

Facebook: www.facebook.com/LimumuTEKE

Shenshan Aiyu

While Lrimumu Teke is set up on the stone-fenced narrow porch of a slate-façade residence, Shenshan Aiyu is set up in a street-facing courtyard fronted by the traditional-style low stone fencing.

A cooling bowl of aiyu jelly is a favorite Taiwan summer treat. Here it’s combined with another beloved summer tradition, shaved ice, which is served with various sweetened goodies. On the menu are aiyu jelly ice with persimmon and lemon, with fermented millet, and with mung bean, as well as the signature creation, assorted (i.e., all of the above gems) aiyu jelly. In the courtyard is rustic Rukai-style seating at tables/benches made with thick slate slabs, and on the residence’s roof is shaded picnic-table seating from which patrons can look out over the settlement’s lower farm-grid area into the deep valley abyss.

Aiyu jelly is made from the seeds of a creeping vine fig that flourishes in forest 1,200~1,900m in elevation.

Shenshan Aiyu (神山愛玉)

Add: No. 16-1, Shenshan Lane, Wutai Village, Wutai Township, Pingtung County

(屏東縣霧台鄉霧台村神山巷16之1號)

Tel: 0933-684-700

Hours: 9am ~ 5pm (closed on Mon. and Tue.)

Facebook: www.facebook.com/Wutairukai

Majia Township

Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Park

As you approach the gaping Ailiao River valley mouth while crossing the wide Gaoping River plain, you get views of a settlement prominently laid out on a plateau on its north side. This is Sandimen, perhaps the region’s most tourist-visited indigenous village.

Our quest here, however, is the attraction spread out on a plateau on the opposite side, the Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Park. This is one of the world’s biggest theme parks focused on indigenous cultures, with a splendrous scope of knowledge-enhancing and entertaining experiences. There are first-rate replicas of traditional Taiwan indigenous architecture, dynamic song-and-dance performances, a museum dedicated to the potent sculptural artistry of the many different tribal peoples, DIY workshops where you create your own indigenous-style handicrafts, a hiking trail to higher ground and a park overlook, and fresh-cooked native foods aplenty, featuring many ingredients you will no doubt not have come across before.

Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Cultural Park (台灣原住民文化園區)

Add: No. 104, Fengjing, Beiye Village, Majia Township, Pingtung County

(屏東縣瑪家鄉北葉村風景104號)

Tel: (08) 799-1219

Hours: 8:30am ~ 5pm (closed on Mon.)

Website: www.tacp.gov.tw

Rinari Village

Just southwest of the park is Rinari Village, a slopeland settlement that looks over the plains. Western, especially European, visitors will experience a sense of the familiar-yet-exotic here. The neat grid of tidy streets sports copycat-design A-frame and twin homes, all two stories, all wood-built. This young place is a re-settlement of three high-mountain Rukai/Paiwan villages that suffered severe damage in an infamous 2009 typhoon. In striking yet harmonious contrast with the European-style architecture is each abode’s traditional Rukai/Paiwan slate-built patio, complete with low slate-slab fencing and seating, which tribal members call their “living rooms.” The exteriors of many homes are stand-alone artworks, brilliant with etchings, paintings, and drawings depicting the stories, customs, and histories of the resident clans.

The tribe’s younger generation has developed Rinari as a tourist-beckoning attraction, and you can experience guided tours, song-and-dance sessions, handicraft DIY, indigenous-fare dining both simple and upscale, and home-based shops selling traditional-style crafts created by masterly matriarchs.

Liangshan Recreation Area

The area’s lower section is primarily family-oriented: a visitor center, small park with swings and whimsical installation artworks, pond with resident honking geese, camping facilities, oh-so-cute “Hobbiton village,” goat enclosure and, where the valley narrows dramatically, large covered rest facility where fresh-made lemon aiyu jelly, local-fruit juices, coffee, and tea are sold (weekends/holidays). The visitor center, decked out with an alluring indigenous-symbol theme, has English brochures, hands-on displays of tribal attire and handicrafts, and a large, well-wrought regional scale map (all places in this article are within the Maolin National Scenic Area; maolin-nsa.gov.tw).

This usually serene recreation area is located right off County Highway No. 185, which moves north-south along the base of the mountains. It takes up a narrow low-mountain valley, stretching from the valley’s mouth where it debouches onto the plains all the way up to its head, about 2.5km inland, where the isolated, multi-tiered Liangshan Waterfall tumbles in seeming slow motion into a tight gorge piled up with massive boulders.

You enter an utterly different world in the upper valley, traversing the 1.5km Liangshan Trail. The walls come in ever closer, the hillsides become ever steeper and climb higher and higher. The first trail section is mildly demanding boardwalk stairs, which lift you high up the south-side cliffside. After this the grades are easy, and the valley bottom steadily rises up to meet you. While zigzagging along in the shade provided by the dense forest, a bonus (on relatively hiker-light days) is the incessant song of the wild birds.

Liangshan Recreation Area (涼山遊憩區)

Add: No. 14-20, Liangshan, Liangshan Village, Majia Township, Pingtung County

(屏東縣瑪家鄉涼山村涼山14-20號)

Tel: (08) 799-3520

Hours: 8am ~ 5pm (from 7am on weekends and holidays)

Facebook: www.facebook.com/liangshan.co

About the author

Rick Charette

A Canadian, Rick has been resident in Taiwan almost continually since 1988. His book, article, and other writings, on Asian and North American destinations and subjects—encompassing travel, culture, history, business/economics—have been published widely overseas and in Taiwan. He has worked with National Geographic, Michelin, APA Insight Guides, and other Western groups internationally, and with many local publishers and central/city/county government bodies in Taiwan. Rick also handles a wide range of editorial and translation (from Mandarin Chinese) projects.