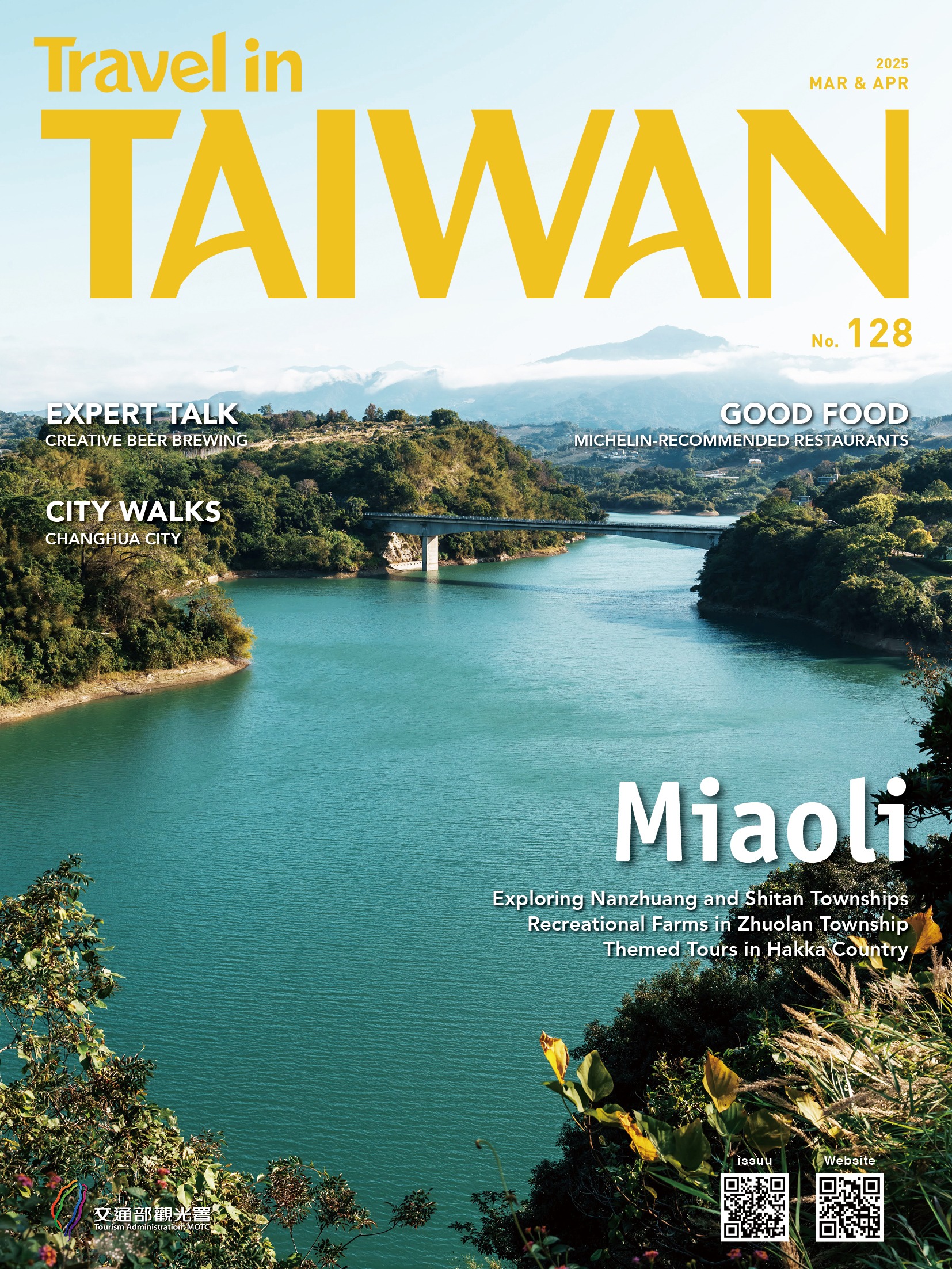

Mountain scenery near Shanmei Village in Southern Alishan

Big blue skies + deep green valleys + small indigenous villages + Tsou Tribe culture + easy mountain trails + organic farming + twisting, rugged rivers, and streams = the “hidden-away” region of Southern Alishan.

Text: Rick Charette, Photos: Ray Chang

The beauty of the exceedingly popular Alishan National Scenic Area, one of Taiwan’s most iconic tourist destinations, lies in its timelessness. The foundation elements that attract lovers of things natural and pure and non-materialistic have been in place long before tourists began to arrive, long before any settlements took shape, long before any member of the human race set foot on this upward-thrusting mountainous island. Visitors can see that all of the human-created modern elements enjoyed here are built on this base.

Most travelers explore the national scenic area’s central corridor, stretching from the western plains by the foot of the mountains near Chiayi City to the Alishan National Forest Recreation Area along Provincial Highway 18. The famous Alishan Forest Railway, which starts in Chiayi City, ends in the forest area. We most recently explored this region in our March 2014 issue.

At the Alishan Forest Recreation Area

Travel in Taiwan has also explored Alishan’s quieter northern region, in our March 2016 issue, most easily reached from the central corridor via County Highway 169, which passes through the town of Fenqihu, half-way station on the tourist-popular narrow-gauge alpine railway.

In this issue we explore Alishan’s southern region, which is quieter still. You turn onto County Highway 129 from Provincial Highway 18 at Longmei village, long before reaching the great heights of the Fenqihu area and, higher still, the forest recreation area. You are traveling down into a long, twisting valley area that debouches at the western plains at the lovely Zengwen Reservoir. The rugged Zengwen River snakes along the valley floor. High on the valley sides are small farming villages. Most residents here are from the Tsou Tribe, which calls Alishan home, along with members of the Bunun Tribe and Han Chinese.

Helpful Hint: Don’t bypass the expansive Alishan NSA Chukou Visitor Center before you begin your mountain ascent. On the outskirts of Chukou town, where Highway 18 leaves the plains to begin its skyward climb, the extensive English-language display, video, and brochure information will greatly enrich your time at Alishan.

Alishan Visitor Center near Chukou

Shanmei

On a recent 3-day self-drive outing to Alishan’s southern villages we (me and three companions) reached the Highway 18/129 junction about four hours after leaving Taipei. We spent the remainder of our first day exploring the Shanmei community, from the mountain-ridgeline junction down to the Zengwen River, almost always in view far down below. Shanmei is spread out in a number of clusters along the highway, and beside the Zengwen is its most famous attraction, Danayigu Ecological Park.

Danayigu Ecological Park

We met up with our guide for the afternoon – Mr. Zhuang Xin-ran, from the Tsou Tribe (contact the Shanmei Community Development Association; (05) 258-6994/258-6621 to arrange guided tours of Shanmei), sporting the long locks traditionally worn by native braves, and had lunch at Yupasü Tsou Tribe Restaurant. This is an inviting timber-built eatery beside the highway about ten minutes from Longmei, in the first neighborhood cluster of Shanmei. The valley and mountain vista out beyond the dining-area deck is deliciously appetizing. “Yupasü” is a Tsou term meaning “to grow wealth,” chosen to invite fortune by the owner. The food is hearty, well-prepared, and well-presented; this is the only place in the southern villages with anything like a chef in the kitchen. I have a hopeless “sweet tooth” for indigenous-style boar (wood-grilled here, not the common stone-grilled), but to be honest, the most unusual item on the menu was also the most satisfying – marinaded charcoal-grilled turtledove. The price per adult is NT$250; you’re presented with a banquet-style set meal according to group size; smallest of which is for 2~3 people, consisting of five dishes.

Our Alishan guide for the day: Mr. Zhuang Xin-ran

Yupasü Tsou Tribe Restaurant

Wood-grilled meat and bamboo tube rice

Add: No. 1~8, Neighborhood 1, Shanmei Village, Alishan Township, Chiayi County (嘉義縣阿里山鄉山美村1鄰1之8號) Tel: 0919-318-959

After our meal, Mr. Zhuang brought us around Shanmei’s sections and the eco-park. Shanmei’s elevation ranges from 500 to 1,200 meters (by way of reference, Alishan National Forest Recreation Area sits at about 2,200 meters). Almost 100% of Shanmei residents are Tsou. The nanshancun or “south mountain villages” area was originally a hunting ground for Tsou from the tribal villages of Lijia and Dabang to the northeast. Shanmei had about 30 households before 1929, but was formally established in that year, during the Japanese colonial period (1895-1945). Han Chinese had also been moving in, to log the local camphor trees.

Mural in Shanmei Village

Today you’ll see bamboo forest all around; though there have been other sources of income, such as ginger, taro, corn, jelly fig, etc., and in recent decades high-mountain tea. But it has been bamboo, for both culinary and other uses, that has been the main source of income. Since the eco-park’s establishment, the area’s commerce has been slowly shifting toward tourism and recreation.

The majority of the Tsou, who number about 7,000, live in Alishan Township. The tribal word tsou, which means “human being,” was in fact chosen as the group’s name by Japanese anthropologists, and thereafter gradually adopted by tribal members and government. The tribe’s original home area was on the western plains, in the Tainan region. In tribal lore the Alishan move was either made after warriors found ample game here or to escape Dutch colonial persecution in the 1600s. Major traditional festivals include the annual Millet Harvest Festival (Homeyaya) and Mayasvi, holiest of all Tsou religious celebrations, which involves Tsou-deity welcome and sendoff rituals, Cleaning of the Paths rites to drive out evil and maintain communication with the gods, an Adulthood Ceremony, and other symbolically rich traditions. Members of Alishan’s Tsou tribe

Danayigu Ecological Park is just a young sapling compared to Alishan’s other major tourist attractions. Visitors here are proffered a feast of music and dance performances by native Tsou singers and dancers, a historical photo exhibit educating visitors on life in the south villages region, and a delicious harvest of native culinary delectables and souvenir buys at a collection of native-theme eateries and handicraft shops.

Indigenous-culture performance at Danayigu

The main attraction, however, lies beyond the entrance area. A forest walk of just a few hundred meters brings you by the Zengwen River and Danayigu Stream intersection. The new very long and very camera-friendly, dramatically situated Danayigu Suspension Bridge shoots the latter at its base. The Zengwen gorge here is breathtakingly narrow, that of the Danayigu even more so. Mr. Zhuang and other locals repeatedly told us how the valley resembled a Garden of Eden before the devastating and all-changing Typhoon Morakot in 2009; photos in the photo-exhibit hall prove this true. Today’s boulder-block valley, however, is a place with images perhaps even more powerful.

Danayigu Suspension Bridge

The eco-park is a precious habitat for the rare shoveljaw carp, an endemic species almost hunted to extinction just a few decades ago. We were politely told “outsiders” used poison and electrocution without restriction, which also threatened the local fresh-water supply. Tribal elders convinced fellow members to contribute their traditional lands to the establishment of the eco-preserve in the 1990s, and since then locals have organized patrols, and the carp have thrived. Valley tourism has concomitantly thrived, and Shanmei has become a model for regional eco- and tribal tradition-friendly, tourism-savvy development.

Feeding shoveljaw carps at Danayigu

Shoveljaw carps

Now, let’s move back in time a bit. As you navigate the highway downhill from the last Shanmei neighborhood toward the eco-park, just before crossing the river you encounter a scene stirringly dramatic. Far off beyond you see the Danayigu Suspension Bridge, below you see two side-by-side bridges jumping the Zengwen; the earlier bridge, though not old, was closed after a typhoon weakened it; the newer one is handsome white-colored Shanmei Bridge. To your right is lofty Fumei Suspension Bridge. You can park your car by the viewing pavilion on the far side and enjoy the changing views from along the highway bridge. Then walk along the main road up to one end of Fumei Suspension Bridge.

Shanmei Bridge

Fumei Suspension Bridge is Taiwan’s longest hammock-style suspension bridge. Stretched 175 meters and soaring 80 meters above the river, it sports the iconic colors of the Tsou – red, blue, and black. Mr. Zhuang informed us that during Typhoon Morakot the river water came up to the height of the cables hanging under the bridge.

Fumei Suspension Bridge

Crossing the bridge, you come to the “Mountain Beauty” restaurant. There we enjoyed a hearty indigenous-theme meal overlooking the bridges on a large open-air clifftop deck. The restaurant primarily caters to tour-bus groups but has single-diner options. Savor fare such as grilled salted range chicken and mountain-boar sausage, fresh mountain vegetables and fruits, plus Alishan Oolong tea (chicken set menu NT$280, pork NT$250).

“Mountain Beauty” restaurant

Dinner at “Mountain Beauty” restaurant

Add: No. 106, Neighborhood 6, Shanmei Village, Alishan Township, Chiayi County (嘉義縣阿里山鄉山美村6鄰106號 Tel: (05) 258-6655

Another Helpful Hint: If not with a guided tour-bus group, use of local guides is strongly recommended – in my opinion, requisite. The cost for a local guide (Chinese-speaking) is NT$1,000~$2,500 for 2~4 hours, itinerary custom-tailored to time/fee. Contact information is provided in each village section.

Beautiful scenery between Shanmei and Xinmei

Xinmei

The Xinmei community sits at an elevation of 400-800 meters. Following Shanmei’s lead, sightseeing attractions are being systematically developed to showcase the distinctive local character. What has emerged as the foremost attraction is Xinmei’s organic agriculture.

During the Japanese era, the riverside flatland areas below present-day Xinmei village were developed for, primarily, paddy-rice agriculture, the farmwork handled by Han Chinese. After WWII and the Japanese departure from Taiwan, Tsou members from Dabang and Lijia were encouraged to move in, engaging in small-farm agriculture and raising cattle.

The processing facilities of the collectively-run Daso Ci Cou Organic Agriculture Development Association sit on a highwayside plateau overlooking the Zengwen just past the main Xinmei village cluster. Local farming families began turning to organic cultivation in 2005, after coming to understand the harm that standard practices had been causing to their living environment. Our Xinmei guide, Ms. Yang Pei-zhen, explained the cooperative’s philosophy and its cultivation and marketing methods while giving us a tour of the fields behind, processing facilities, and sales area.

Guide Yang Pei-zhen on organic farm in Xinmei

Among the tasty items I brought home were the chili paste (NT$150/jar), marinaded mountain-bamboo chunks with peanuts (NT$150/jar), and dried bamboo chunks dusted with ginger powder (NT$100/bag). You can enjoy self-picking and other DIY experiences, and will soon be able to picnic at the facility, with either self-picked or ordered items cooked for you on-site.

Produce of Xinmei

Add: No. 51, Neighborhood 3, Xinmei Village, Alishan Township, Chiayi County (嘉義縣阿里山鄉新美村3鄰51號) Tel: 0929-296-561 (Ms. Yang)

Ms. Yang next took us on a pleasant tour of the Camphorwood Forest Trail, which begins at the highway just above the farm, takes you up and over a ridge, and drops you off back on the main road right beside Xinmei village. This rebuilt 2.4km trail was originally blazed by Tsou hunters headed up-mountain; you’ll see an example of the traditional mini-huts they would hide in by the trailside, along with the occasional elaborate traditional-style bird snare. In the trail’s central section is an oil-tree camellia plantation, cultivated since the Japanese era, and higher still a highly aromatic camphor-tree plantation.

Pavilion on Camphorwood Forest Trail

After our descent Yang introduced the village, showing us, among other things, the eclectic old village church – the majority of Taiwan’s tribal members are Christians – and the oldest mom-and-pop general store in the south villages region (by the way, there is no chain-franchise businesses of any sort in this area), today run by the third generation, where the tribal-elder owner enthusiastically pulled out every English word accumulated over his lifetime to talk with us. Though he came up well short of 50, we had a great conversation nonetheless.

Old church of Xinmei

Xinmei seen from a distance

Chashan

In Chashan village, our first stop was the cultural-activity ground diagonally across from the Chashan Development Association office, where a bus-tour group was being edu-tained with indigenous song and dance, shooting a wild-boar cartoon figure with bow and arrow, making indigenous-style mochi with mortar and pestle, sampling bamboo-tube rice and fresh-grilled meats, etc. After trying out some of the fun for ourselves our designated guide, a young and impressively knowledgeable Tsou maiden named Ms. Chen Xiao-lin, took us on a tour of Chashan.

Tour bus tourist entertainment at Chashan

Add: No. 77, Neighborhood 4, Chashan Village, Alishan Township, Chiayi County (嘉義縣阿里山鄉茶山村四鄰77號) Tel: 0921-242-185 (guide service: Mr. Fang) The friendly folks of the Chashan Community Development Association

First up was the activity ground’s Alishan-theme gift and souvenir shop, where she introduced Alishan specialty items. I came away with a half-pound of Alishan black tea leaf (NT$800), bitter-tea oil (NT$1,200/bottle), and high-mountain cane sugar (NT$200/jar).

Bitter tea oil

Chashan, Alishan’s most southerly village, ranges from 260 to 1,600 meters in elevation. The unusually high number on the back end is explained by the fact that the main village cluster is on the lower reaches of Mt. Zhuowu, but the village’s area in fact reaches right up to the mountain’s top.

The village’s original Tsou name means “plain on the mountain mid-slope.” The Japanese once raised horses and cattle here; today the village sits on the plain, inhabited by Tsou, Bunun, and Han Chinese, in a rough 60/30/10 mix. Large woodcarvings line the streets, each explaining elements of the Tsou culture.

Chashan Village seen from higher up

It also seems that everywhere you look you see a timber-frame rest pavilion with thatch roof, each with its own distinctive character. Each of the three groups builds them, but their origin is with the Tsou. Called hufu in the Tsou language, in days past meat obtained in hunts would be placed inside to share among village families. They are built today to celebrate the traditional indigenous sharing culture, and the practice now is to hang locally grown plantains instead of meat. Tourists are welcome to take one each. Note that some hufu are private, identified as such by the wild-boar skulls and jawbones hung up; you’re welcome to enter, but ask permission first.

Traditional Tsou tribe pavilion

Coffee-lovers cannot get past the On This Mountain Studio/Guesthouse/Cafe, a short walk along the road behind the activity center, overlooking neat farm fields. Run by an artist couple, husband Tsou, wife Hakka, artworks pervade the premises – your coffee is served in the wife’s handmade mugs, each unique and right from a Lord of the Rings scene.

On This Mountain Studio/Guesthouse/Cafe

Coffee served in handmade mugs

The Tun’abana Trail, shaped like a figure 8, is 2.3km long. At its start and end it directly overlooks Chashan village. The key attractions along the way are the Jiayama Fall and Fire and Water Spring. The former shoots out from thick forest but, dramatically, immediately disappears below the pool at its base. Ms. Chen informed us that the original channel is still followed, but it’s below a thick cover of earth and rock washed down by Typhoon Morakot, the waters reappearing out of sight beyond.

Going for a walk on the Tun’abana Trail

At the Fire and Water Spring

At the latter, natural gas and water well up through crevices, igniting naturally despite the water’s presence. Chen taught us the traditional call given by returning hunters when emerging from the forest high above the settlement, and to our delight all the kids we spotted in town immediately looked up and hollered the traditional welcome.

Chashan resident

High above Chashan’s main settlement are two places worth mentioning. Both can be reached by taking minor roads up the steep side of Mt. Zhuowu. At Chun Ye Yuan homestay tea-hill.ho.net.tw; Chinese), enjoy a unique farmstay experience with a family that cleared their land over 50 years ago and lives in a traditional three-sided courtyard-style farmhouse. The friendly owners serve a hearty traditional dinner and breakfast made with fresh vegetables, fish, and other items produced on the farm. A short walk uphill from the farmhouse is a great lookout spot from where you can enjoy a breathtaking 270-degree panoramic view over Chashan and the surrounding mountains.

Entrance to Chen Ye Yuan homestay

At lookout spot uphill from the homestay

Further uphill from the farm homestay, and just below the mountain’s top, is the award-winning, tourist-inviting Zhuo-Wu Mountain Café Grange coffee farm. Here you can walk amongst coffee trees, learn about organic coffee cultivation, and sample award-winning Taiwan coffees of the highest quality. If interested in trying the coffees without visiting this faraway spot, note that the owner-family operates a café in Chiayi City. (Zhuo-Wu Café; No. 194, Minsheng N. Rd., Chiayi City / 嘉義市民生北路194號; tel.: [05] 222-5896; www.facebook.com/ZhuoWuCafe)

Zhuo-Wu Mountain Café Grange coffee farm

Preparing high-quality Taiwan coffee

From Chashan, highly recommended is making the short drive down along Zengwen River to the picture-perfect Zengwen Reservoir, then heading north along Provincial Highway 3 to its connection with Highway 18. Whereas much of Highway 3 features substantial and sometimes heavy roadside development, this stretch is one of pristine and oft thrilling mountain views, along with arrestive, commanding looks over the western plains as you get closer to Highway 18. Happy trails.

Zengwen Reservoir, seen from Provincial Highway 3

The Taiwan Tourist Shuttle service (taiwantrip.com.tw) runs two routes into the Alishan National Scenic Area (see our previous Alishan articles). However, public transportation is not an option in the Alishan southern region. For groups, a bus tour with an English-speaking guide custom-tailored by a local Taiwan Tourism Bureau-vetted travel firm is recommended. Visit the Taiwan Tourism Bureau website (Taiwan.net.tw; Taiwan Tour Bus section) for more information. For DIY travelers, car rental is the best option; service desks are found in the THSR (Taiwan High Speed Rail) Chiayi Station, and rental offices are located right outside the Chiayi Railway Station.

Spiritual Travels (by Nick Kembel):

Alishan, Taiwan: Best Sunrise Spots, Hiking Trails and Tea Farms

About the author

Rick Charette

A Canadian, Rick has been resident in Taiwan almost continually since 1988. His book, article, and other writings, on Asian and North American destinations and subjects—encompassing travel, culture, history, business/economics—have been published widely overseas and in Taiwan. He has worked with National Geographic, Michelin, APA Insight Guides, and other Western groups internationally, and with many local publishers and central/city/county government bodies in Taiwan. Rick also handles a wide range of editorial and translation (from Mandarin Chinese) projects.