One of the most Thrilling Festivals in Taiwan

TEXT / STEVEN CROOK

PHOTOS / YANSHUI WU TEMPLE, VISION

Once a year, a small town in southern Taiwan “explodes.” Or so it might seem to those fearless onlookers who subject themselves to the attack of thousands of mini rockets fired at random into the skies and into the crowds from beehive-like structures. Those who have “done” Yanshui and left the festival unscathed enjoy bragging rights for life, and should not miss any opportunity to tell their grandchildren all about it.

It had been exhilarating, unlike anything I’d ever experienced. First, the sounds. The eerie creaking of the sedan chair as temple volunteers — like me covered head to toe in protective gear — swung and rocked the icon over a pile of burning spirit money. That was followed by the stewards’ whistles as they tried to push the crowd back.

Then the strange silence. When the sedan chair was in position, a few meters in front of a paper-covered frame as big as a truck, the thousands-strong crowd fell silent. Once the technicians had torn off the squares of red paper we could see what lay inside: row upon row of bottle rockets pointing not at the sky, but at the sedan chair and us in the crowd.

(Photo courtesy of Wu Temple; photographer Su Lian-ji/蘇連吉)

When the fuses were lit, people didn’t have to be told to move back. Some tried to take cover behind streetlights; the short cowered behind the tall. The opening shots, however, were into the sky. There were, as you’d expect at a fireworks display, lots of pretty explosions high above the rooftops.

Then rockets came blasting out horizontally. At first they fizzled like tracer bullets over the heads of the audience, but within a second or two the angle of fire was much lower.

(Photo courtesy of Wu Temple; photographer Zheng Xue-rong/鄭雪容)

Instinctively I turned away from the frame and felt multiple impacts on my back. The physical feeling, I thought at the time, was somewhat like being chased by a stone-throwing mob — not that I’ve ever actually had that type of misadventure. But mentally it was utterly different: It was thrilling and compelling. In addition to tremendous excitement there was fear, to be sure, but none of the sickening dread you might feel when confronted by violent people.

Rocket skidded of the road surface and struck my shins. A few ricocheted off buildings and fell harmlessly on my shoulders. When the bombardment stopped there was a roar of appreciation from the crowd. Some people high-fived their friends; others pumped their fists, giving vent to an adrenalin surge.

(Photo courtesy of Wu Temple; photographer Zheng Guang-feng/鄭光烽)

I recognized a friend as he rushed up to me and thumped me several times on the shoulder and chest. Because I couldn’t see his face — like me he was wearing a motorcycle helmet with visor down — I assumed he was congratulating me on having come through unscathed.

Only when I took my helmet off a minute or two later did I realize what had happened. The old towel I’d wrapped around my neck to stop rockets getting inside my helmet was half-charred and still smoldering. I pulled out my earplugs just in time to hear my friend tell someone my towel had been burning “good and proper.”

Rockets catching in the folds of your clothes and setting them alight are just one of the hazards faced by those who join the annual Yanshui Beehive Rockets Festival. Temporary loss of hearing from the thousands of firecrackers is another; hence the earplugs. Your toes will get trampled, as the crowds can be incredibly dense. And despite whatever you attempt to avoid it, you’ll breathe in vast amounts of acrid smoke.

(Photo courtesy of Wu Temple; photographer Ye Shi-xian/葉世賢)

Each year a few dozen of the 50,000 or more who attend the festival require hospital treatment, though serious injury is rare. If you prepare properly, the odds are very much in favor of your having a fantastically memorable time, and coming out of it with nothing worse than aching legs. You can protect yourself against the fireworks, but there’s no avoiding the hours of walking and standing up.

But before we discuss preparations, let’s delve into the history of what’s almost certainly the most extreme and exciting pyrotechnics event in the world.

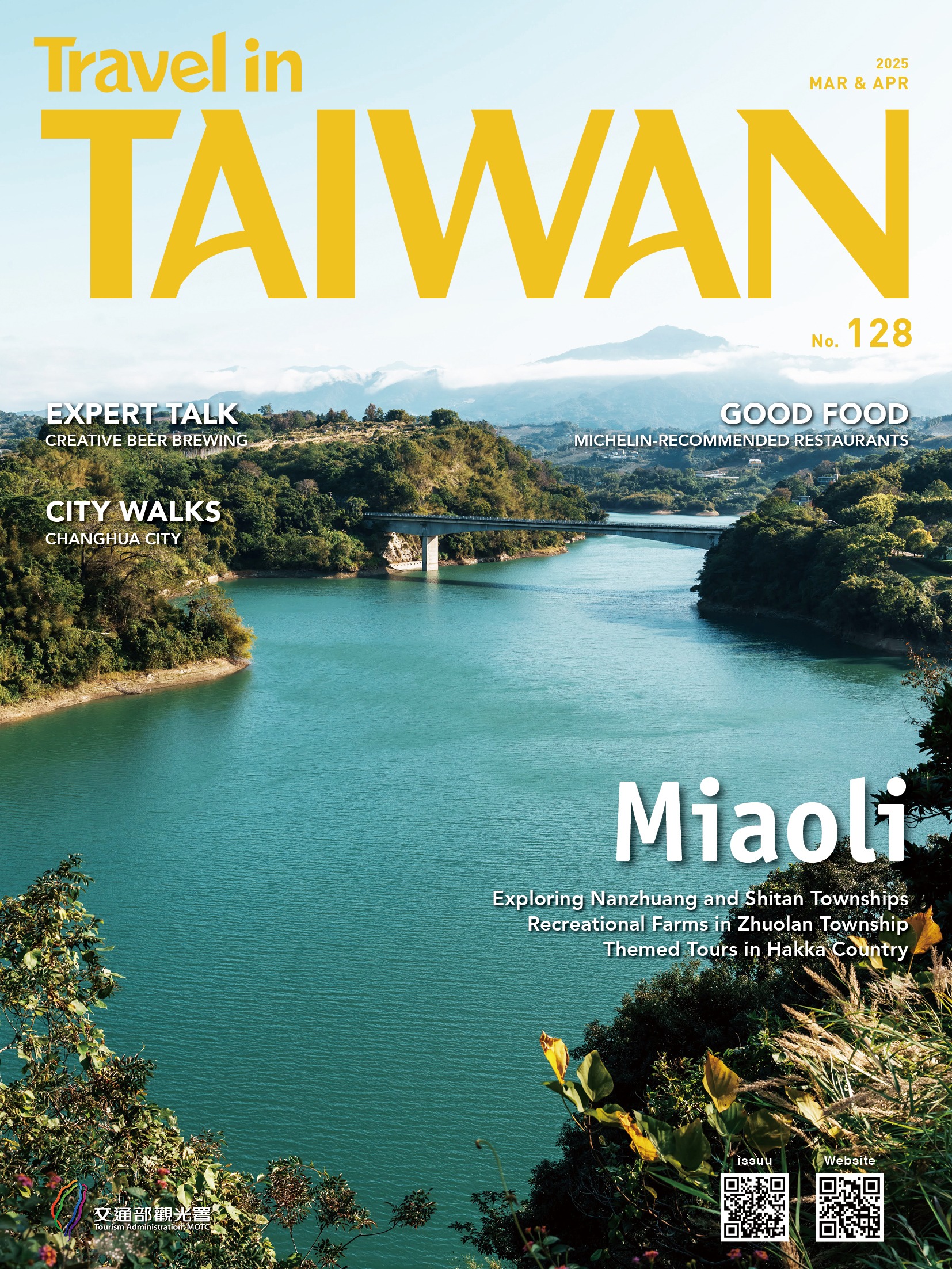

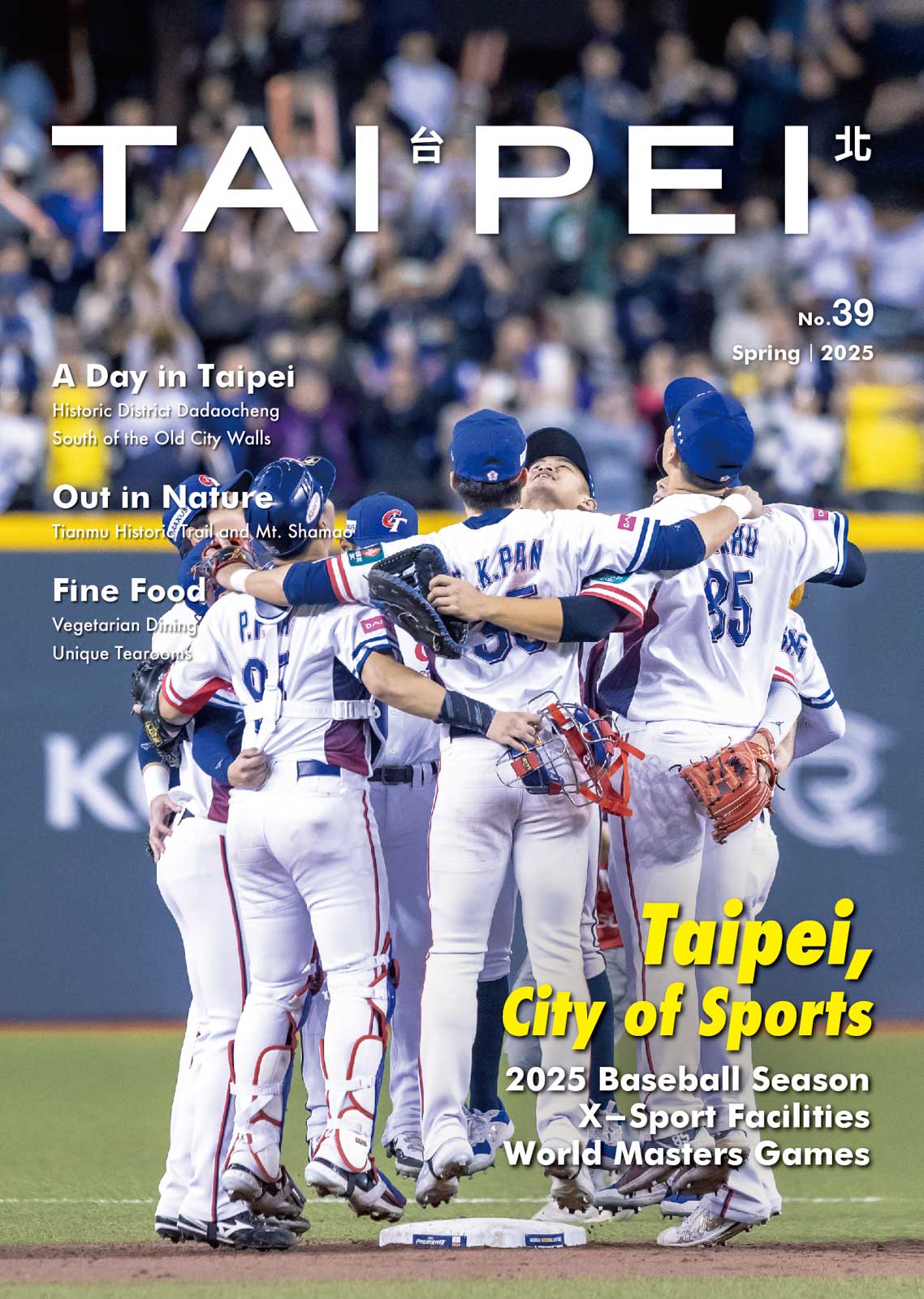

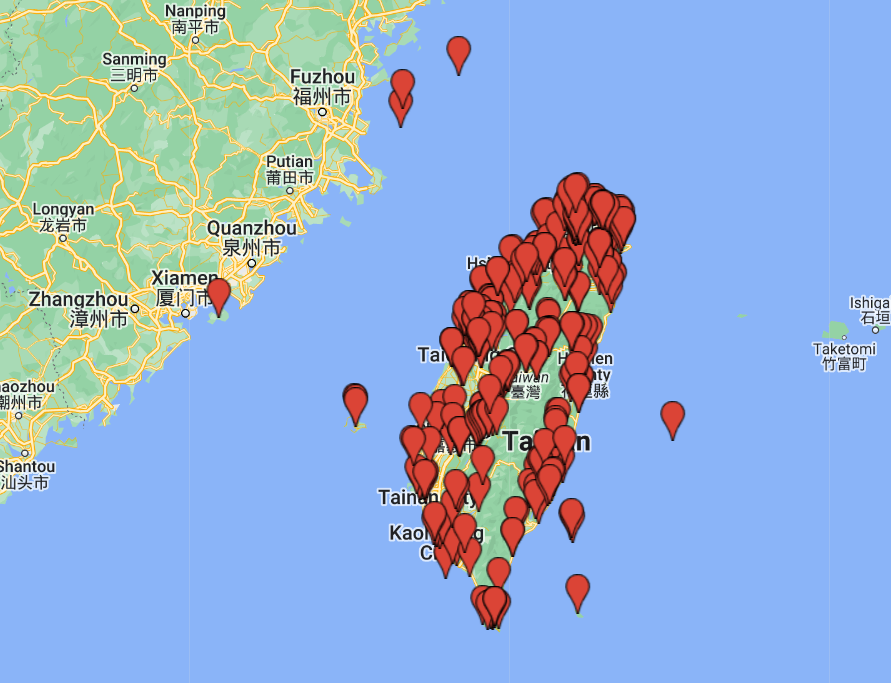

The Yanshui Beehive Rockets Festival — you’ll sometimes see “fireworks” substituted for “rockets” in the title — is held 15 days after Lunar New Year in the small town of Yanshui (population 28,000) in the northern part of Tainan City. It coincides with the Lantern Festival, but isn’t related to that celebration.

It’s somewhat fitting if third-degree burns, bruises, and close shaves remind festival participants of their mortality, as the event’s history is thoroughly gruesome. The festival reenacts a plague-expulsion rite. More than a century-and-a-quarter ago, an outbreak of cholera wreaked havoc on Yanshui, then a prosperous harbor town and one of Taiwan’s four main commercial centers. (The others were the ports of Tainan, Bangka in Taipei, and Lugang in Changhua.)

(Photo courtesy of Wu Temple; photographer Wang Ming-ren/王明仁)

Neither physicians nor shamans could defeat the epidemic. In desperation the local residents called upon their gods to drive out the evil spirits they blamed for the pestilence. Townsfolk carried through the streets an effigy of Guan Gong, a deified imperial general also known as Guan Di and Guan Yu. He’s regarded as the Chinese god of brotherhood and righteousness, as well as the God of War.

At every turn citizens let off masses of firecrackers. This exorcism seemed to work; the epidemic soon receded. Ever since, there have been annual parades, sponsored by local businesses and temples. Participation is free; residents cash in by selling snacks, soft drinks, and protective attire.

The festival now includes folk-arts performances and other activities spread over two or more days. The fireworks parade, by far the most popular part of the festival, usually begins around dusk on the 15th day of the first lunar month, and continues until dawn the following day.

There’s no shortage of religious fervor among middle-aged country folk in Taiwan. (If you doubt that, visit Nankunshen Daitian Temple, 15km southwest of Yanshui, on any given Sunday.) However, most of those who go to the Beehive Rockets Festival are of college age, and attend for kicks, not for reasons of piety.

If you have any intention of getting close to the front line, wear a full-face motorcycle helmet, thick clothing (avoid nylon garments for obvious reasons), thick gloves, and sturdy footwear. Leave no flesh exposed, even if it means you swelter.

(Photo courtesy of Wu Temple; photographer Li Xiu-qin/李秀勤)

As soon as a beehive is emptied of its rockets, do what experienced festival-goers do. I call it “the Yanshui shuffle.” Shake your limbs vigorously and stamp your feet for several seconds, to shake loose any smoldering fireworks that might be trapped in the folds of your clothing before they can set you alight. Had I known about this the first time I joined the festival, that towel might still be intact…

Your safety is entirely your responsibility. In the hours before the first beehive is set off, small trucks sponsored by the local government drive around Yanshui displaying posters and using audio recordings to instruct festival-goers how to dress. However, the police — who have enough on their hands directing traffic, evacuating casualties, and dealing with those who’ve had their pockets picked — don’t turn away individuals who come unprepared.

(Photo courtesy of Wu Temple; photographer Fan Hui-ling/范慧玲)

I’ve “danced with the bees” several times during my nearly two decades in Taiwan, but it’s only been in the last three or four years* that I’ve come to recognize just what a charming and history-filled town Yanshui is during normal, non-festival times.

If you prefer living, breathing antiquity and countryside quaintness to warzone pandemonium, visit Yanshui on any of the 360 days per year when the townsfolk aren’t gearing up for, holding, or tidying up after the Beehive Rockets Festival.

Explore the back streets; visit the temples; wander down Qiaonan Old Street, which is lined with 19th century abodes; visit the photogenic eight-sided stone-and-wood mansion known as the Octagon Tower; and eat a bowl of yimian, a simple but tasty noodle dish that’s the town’s signature culinary creation.

If you decide the festival isn’t for you — perhaps because you lack the stamina (and recklessness?) to walk and be shoved around in an unfamiliar town for hours on end — but you still want to get a taste of the event, go online. You’ll find plenty of clips on YouTube.

During the festival, non-residents are barred from bringing vehicles into the downtown area. Finding a parking space on the outskirts isn’t difficult, and reaching the town by public transport is straightforward. Lots of trains stop at the nearby town of Xinying (the fasted express service takes three-and-a-half hours from Taipei; from Kaohsiung the travel time is sometimes less than an hour), from where you can catch a local bus or a taxi.

If you leave Yanshui after midnight but before dawn, the best way to return to Taipei or Kaohsiung is to catch a taxi and tell the driver you want to take a freeway bus. And don’t worry about going hungry or thirsty — wherever Taiwanese people gather, there’s plenty to eat and drink!

About the author

Steven Crook

Steven Crook, who grew up in England, first arrived in Taiwan in 1991. Since 1996, he’s been writing about Taiwan’s natural and cultural attractions for newspapers and magazines, including CNN Traveler Asia-Pacific, Christian Science Monitor, and various inflight magazines. He’s the author of four books about the country: Keeping Up With The War God (2001), Dos And Don’ts In Taiwan (2010), Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide (2010), and A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai (2018)

http://crooksteven.blogspot.com

http://bradttaiwan.blogspot.com