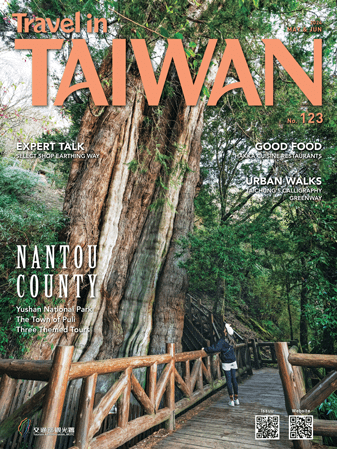

Key Weaver of Taiwan’s Magnificent Cultural Tapestry

TEXT / RICK CHARETTE

PHOTOS / VISION

After more than four hundred years on the island, Taiwan’s Hakka people still exist as a solid and unified community. Their famous work ethic, love of education, and cultural, political, and other contributions have been central in the creation of the island’s sociocultural masterpiece — the wonderful and distinctive mosaic of peoples and free individual expression that its inhabitants are weaving together. Here is the story.

They number about four million, about 15% of Taiwan’s population. Their path through history is shrouded in mist and mystery, but a general map can be drawn. It is thought they came south in stages from China’s northern regions, in the great southward Han Chinese migration. Moving into the hilly areas south of the Yangzi River, en masse yet in stages, their other Han Chinese brethren did not then see them as being of the same race, though in fact the Hakka share most physical/ cultural traits.

The Hakka believe themselves northerners, direct descendants of nobility from the Yellow River cradle of Chinese civilization. When moving south they were shut off from prime land in flat areas and forced to move uphill (some content they “naturally” did so, having also lived in northern upland regions), developing skills and sociocultural traits “natural” to the working of poor high-hill soil and excelling in mining and forestry. Their dialects are southern and young in origin (two are spoken in Taiwan), showing traces of other Chinese dialects. The term “Hakka” or “guest people” is of Cantonese origin.

Migrating to Taiwan

In the 1600s when the great Chinese migration to Taiwan from southeast coastal China began, the settlers seeking to escape overpopulation, poor and exhausted soil, and official oppression, the Hakka, especially those from northeast Guangdong’s rugged hills, jumped at their window of freedom. Leaving China was illegal for all for much of the 1600s, for the Hakka specifically some time after 1683. They remained close-knit, and their communities came into conflict with their south Fujian or “Minnan” (“south of the Min River”) neighbors even more often than back home.

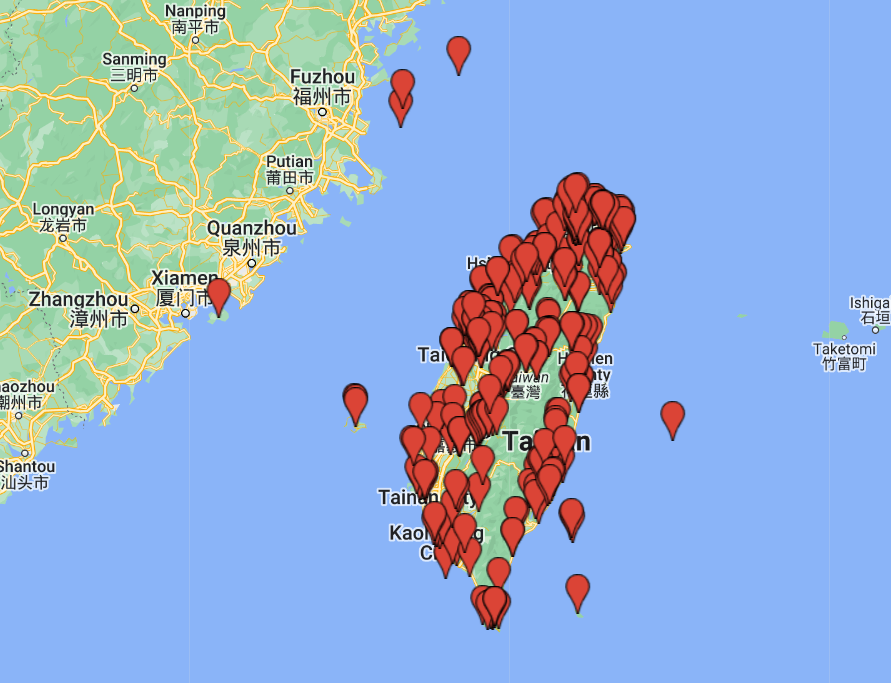

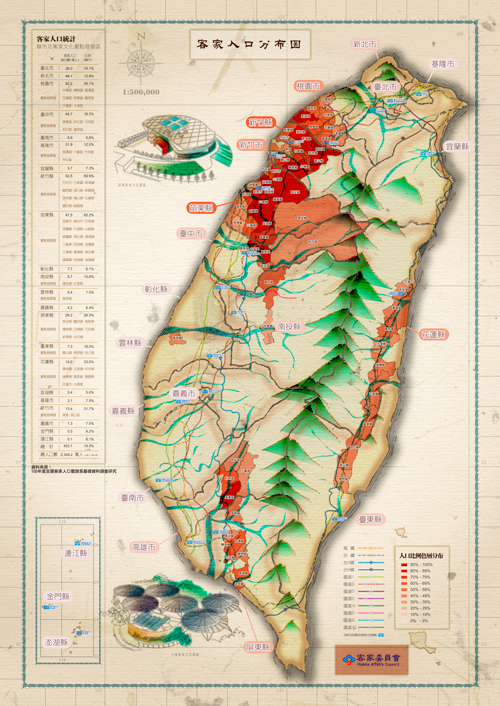

Heavily outnumbered, they eventually became primarily concentrated in two areas — in the western foothills of north Taiwan in Taoyuan City, Hsinchu City/County, and Miaoli County, and in the south in Kaohsiung City and Pingtung County. In this environment their hard-won highland skills came into full play, and they survived as solid communities quite cut off from the island’s other ethnic groups until just the past few decades.

Today, Taiwan’s modern economy draws Hakka and other youth to the city, affecting solidarity. The community now worries that too many youths speak Taiwanese and Mandarin but not the mother tongue, and are forgetting their cultural roots. The island has experienced a passionate “native soil” self-discovery movement in the past few decades, and much interest has been shown in traditional Hakka ways. Official support has come with the establishment of the central government’s Council for Hakka Affairs, Taipei City’s Taipei Hakka Affairs Commission, and public/private groups at other levels. For the foreign visitor, the most important result has been the rejuvenation and/or initiation of Hakka festivals that allow you to jump with both feet into the community’s world.

Defining Cultural Characteristics

In most ways the traditional Hakka reality has been little distinguishable from that of other groups of Han Chinese descent. However, clear differences there have been and still are. Already alluded to is the renowned devotion to family, clan, and community, stemming from the insecurity of long being ostracized as a group. The need to eke out a living from stubborn land led to the Hakka’s renowned frugality (and business acumen).

Hakka women’s feet were never bound. Their help was needed in the fields they fought food from, and Hakka villagers were always ready to flee attack at a moment’s notice — not an easy thing to do with bound feet.

Long shut off from most “flatland” economic pursuits, the Hakka placed even greater emphasis on education than their non-Hakka neighbors — for in imperial times, a successful entrant into the mandarin class could protect an entire clan or village. A favorite expression is “knowledge is better than money.” Community lands and monies would be set aside to support the education of the brightest youngsters, usually male, though basic literacy was widespread. The higher respect the Hakka accorded their womenfolk was clearly manifested in their women’s access to education and their normal feet. The entire country knew the Hakka had a disproportionate number of people in powerful public-sector positions. The stress on educational attainment remains — late president Lee Teng-hui was a prime example and was one of the the island’s best-known Hakka individuals — though it might be said the rest of well-educated Taiwan has “caught up.”

Hakka Food

Isolated Hakka communities grow most of their food themselves, and few fresh vegetables are available in the cool winters. Preserved meats and pickled vegetables are thus common. Another delightful differentiation is vegetables stuffed with minced meat, chili peppers, bitter melon, and so on. The culinary style is characterized by an especially sensitive way of combining only the freshest of crisp vegetables, when available. These are chopped and combined in myriad manners, sauteed/stir-fried lightly to evince the most delicate flavors.

The heavy use of garlic, oils, and spices seen in some other Chinese regional cuisines is avoided. The heavy use of lard that characterizes the Fujianese style is also not found. The frugal Hakka have a dish for every part of an animal; for example, pig’s intestines with ginger slices is a favorite.

The heavy labor of both men and women in field, mine, and forest led to substantial loss of salt, leading to dishes that might strike outsiders as excessively salty. Those cooking for non-Hakka diners these days often hold back on the salt.

Some Hakka dishes, including the two mentioned, were long part of the general local Han Chinese diet, most eaters simply not knowing their origin. Hakka restaurants/eateries have become very popular around Taiwan.

In Hakka “lei” means “grind,” and visitors to private homes have long been greeted with delicious lei tea. Green tealeaves, white sesame, black sesame, and peanuts are ground into powder and mixed together; hot water is then added. Most Hakka eateries will have this on their menu.

Festivals/Religion

The best-known uniquely Hakka religious celebration is the Yimin Festival (Yimin means righteous commoners) one of the few religious festivities to have originated in Taiwan. Commemorated are about 200 brave men who fell fighting an uprising in 1786 in cooperation with imperial officials (and not incidentally defending their own homes and granaries). The mandarins, few in number and corrupt, used to their advantage the tensions between the Hakkas and the rebelling Minnan-ese community.

There remains dispute whether the latter were true “rebels,” since both communities had many legitimate grievances against Qing officialdom, and the two had risen together in a great rebellion some 60 years earlier before turning on each other. In any event, the Hakka use of “righteous commoners” clearly reflects their perspective on matters. The spirits of warriors who died in later-fought righteous causes are also honored.

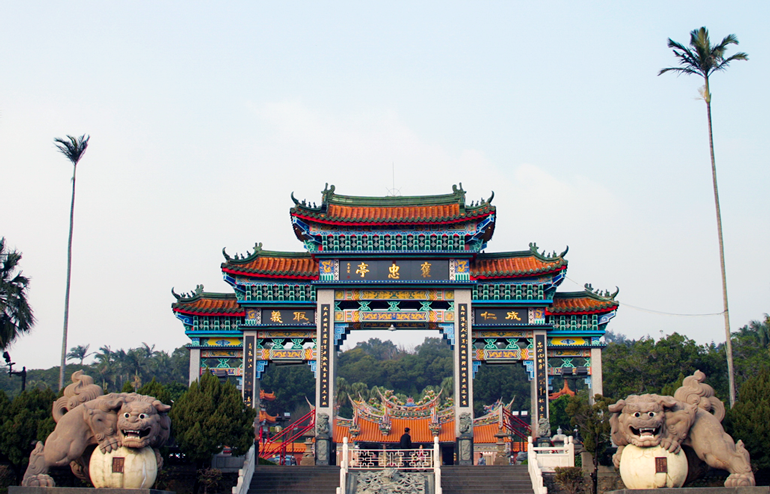

The festival takes place on the 20th day of the 7th lunar month and is centered on the Yimin temples located where Hakka are concentrated. Incense is burned and foods are offered to the spirits, who protect the community. Stages are set up and traditional Hakka opera is performed, each day’s performance launched with a spiritual section, which is religious in nature and specifically aimed at honoring and welcoming ancestors. The celebration is also known for the unique custom of sacrificing “divine pigs,” which are grown to tremendous proportions. Winning sponsors, often families, are guaranteed luck and blessings in the year to follow.

Architecture

Numerous old-style residences are found in the Pingtung town of Neipu and Kaohsiung’s Meinong. The huofang or “semi-enclosed courtyard-style” is most common in Taiwan, with a single main entrance and high exterior walls to enable defense. In a Hakka residence the main hall at the center rear of the courtyard contains the ancestral altar; in Minnan-style homes the hall usually houses an altar for prayer to the gods. Other characteristic Hakka features are the name of the house above the door and three-sectioned walls of white-painted mud brick on top, earthenware tiles in the middle, and stones at the bottom.

Traditional Arts and Crafts

Working on tea plantations, it was common for the Hakka to sing as “talk” to each other. Often this took the form of back-and-forth flirtation between young men and women. From the traditional field songs simple and lighthearted skits took shape, ultimately meshing in the distinctive Hakka opera, often called “three-legged tea picking opera” because no more than three performers take the stage and, in Taiwan, the same tea-theme story is always told, in different versions. No falsetto here — natural voice only. (Incidentally, it is mostly Hakka women who handle the hard work of picking Miaoli’s famous version of Oolung, Oriental Beauty Tea.)

Hakka “grand opera” took shape in the early 20th century, building on the traditional style to revive interest. Elements of other opera forms are incorporated — more performers, colorful costumes, falsetto singing, more riotous musical accompaniment, and different themes (especially historical dramas).

One of the island’s oldest Hakka settlements is Meinong, settled in 1736 deep in a picturesque mountain valley. It is best known for its eye caressing oil-paper umbrellas, perhaps the most visually stunning memento you can take home from your Taiwan voyage of discovery. Featuring an intricate bamboo frame and translucent paper, each is a distinct work of art that is painted with bold, colorful designs and lacquered. They even stop the rain!

The secret of the art — along with the master craftsman tat possessed it — was brought from Guangdong in the early 20th century by a Meinong businessman; the lacquer was changed from dark-brown to yellow and the use of designs was added later. The walk through the town’s main streets, with mountains as backdrop, and open-front shops sporting craftsmen at work, is a trip through time.

Other articles related to the Hakka

LIUDUI HAKKA CULTURAL PARK in Pingtung County

SANYI: History and Hakka Culture in Miaoli

About the author

Rick Charette

A Canadian, Rick has been resident in Taiwan almost continually since 1988. His book, article, and other writings, on Asian and North American destinations and subjects—encompassing travel, culture, history, business/economics—have been published widely overseas and in Taiwan. He has worked with National Geographic, Michelin, APA Insight Guides, and other Western groups internationally, and with many local publishers and central/city/county government bodies in Taiwan. Rick also handles a wide range of editorial and translation (from Mandarin Chinese) projects.